PERSONAL ENCOUNTER WITH DIRECTOR & PROFESSOR SAMIR SEIF

At Nabila Hotel, Mohandiseen, Cairo, Egypt. 14th July 2013.

Samir Seif, an Egyptian film and TV director who rose to prominence in the early 1980s. He was nominated for the Golden Pyramid Award at the Cairo International Film Festival twice, in 1999 and 2002. His directorial debut came in 1977 with the film Ota Ala Nar.

Rosa Pérez, MA student of Middle Eastern Studies at SOAS (2012-2013), went back to Cairo in July 2013 to do some research for her MA dissertation: “Nasserism on the Silver Screen. The use of cinema as a propaganda tool under Nasser’s Egypt”. She used the opportunity to visit Samir Seif in Cairo and interview him about the period from the 50s to the 70s – 80s in Egyptian Cinema and the nationalization of culture. Below are excerpts from that meeting.

Samir: There are two phases when we talk about Egyptian cinema under Nasser’s era. The first phase goes from 1952 to the early 60’s. I mean 61 or 62 before the nationalization of the cinema industry.

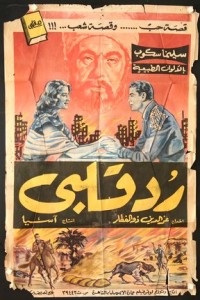

In the first period there was no conscious control of the industry, it came naturally from the filmmakers themselves because it reflected the welcome of the people with the revolution. They welcomed it naturally. By the way, Nasser’s coup d’état, they called it first, by their own language “The blessed movement of the Army”. They didn’t call it a revolution. It was a clear cut coup d’état but they called it the blessed Army movement. But when the people welcomed this movement and demonstrations came supporting it then they dared to call it a revolution and from that moment on, it was called a revolution but first the called it ‘The Blessed Army Movement’. So, there was no conscious control of the industry. It came naturally from the filmmakers. Most of the films of this period reflected the change, the political and social change, I mean, not in a controlled or in an arbitrary way. For example, Yussef Chahine made “Blazing Sun”. It was against the bashas and the feudalism. That was produced not even by a pure Egyptian producer. Rofail Gabour, he was of Syrian or Lebanese origins. Even that was a very filmatesse against feudalism and supporting the fallaheen. It was not dictated or made by the state. For example, the film that was officially the statement of the revolution was a film called “Rudda Qalbi”. “Rudda Qalbi” was made by a director who was originally an officer and comrade of the officers who made the revolution, Ezz Eldin Zulficar. And the first showing of this film was in Studio Misr attended by the Council of the revolution.

It was considered, though it’s naïve in some aspects and very direct, but it has this emotional value and it is considered till now, in our national day 23rd of July, this film is still shown in television today. It is the official expression of the 52 Revolution. And this film, Rudda Qalbi, was produced by a woman, Assia, and she was purely Lebanese. She migrated to Egypt and she was one of the mother founders of the Egyptian industry.

Rosa: So even if it was the highest expression of the Revolution of the 52 it was not always financed by the regime?

Samir: No! At all! It was private producers who welcomed the Revolution and all its attitudes. We can find some tiny expressions, for example, in a not well-known film. It was produced by a star of its time, called “I am love” “Je suis l’amour” “Sono l’amore” (Translated by him) It is completely a small film but it reflected the new attitudes. They shot this film in the royal palaces when they were opened to the public for the first time, I mean in “ElMontaza” it was open for the public, and this film “Ana El hub” was shot there, and in this film the people call each other, as in the French Revolution, no basha, no bek but “ia Sayed Fulan” like citizen, no royal titles or something like that. This is how the revolution was reflected in the films, but this was not dictated by the state. A producer who was an officer, an army officer, Gamal El Lissi he started by making films with the most popular comedian of this period, and this is my personal analysis. He started by making films with this most popular comedian in the different () of the army: In the Army, in the Navy, in the Air force. (Ismail Yassine’s comic films). Of course it has a subtext; welcome with the military spirit and how the army makes a better man out of you. If you were not successful the army gives you the personality, the army gives you the ingredients of manhood, in a very comic way or closer to farce. From my own point of view that was because the producer was an ex-officer and he did not make it by a dictation of the regime but it was part of his belief and of course the authorities helped him a lot in shooting in all these places because it served their purpose, but no dictation, up till this moment, no dictation. No official investment or financing of particular films, no. Only, the Department of Information made some documentaries that were shown in the squares by 16 millimetres projectors, for free, for the people, telling people about the policies of the revolution, about spreading the land on the poor, the fallaheen…and there was even a documentary, a docu-drama, with some actors presenting the officers when the vow on the Koran.

These documentary films were the official input or the official involvement of the government in spreading the ideas of the revolution. (All this happened before the nationalization of the film industry). It came naturally from the producers, from the people, it wasn’t dictated but they welcomed the ideas of equality, of social justice, all that short of things and in a way (laugh) historically, the Revolution or the coup of the officers was backed by the US Embassy. When the Revolution and the coup d’etat happened, the biggest British military base was in Ismaileyya, an hour away from Cairo. They can come easily and spoil the coup but because the United States backed this movement, the British couldn’t move. Though, Nasser later on became the antagonist number one of the United States but that was the American period in Egypt. Because I do remember myself the films, a screening, any show in the cinemas, especially in the popular ones, I mean the second, third but not the 1st (class) ones in Downtown. Before the screening of any film, when lights were coming down, there was a march, music, before the show. What was this music? The Marine’s US march, ta ta tarara tarara[1]. (In the districts, in the popular districts, in the villages, before the screening of any ordinary film). Marine’s marches were played all over the country. Nobody told me, I noticed that. I attended them myself and I was shivering when this music was performed. Of course, for a movie mac or a movie freak like a cinéphile like me of course, that was a ritual; the coming down of the lights, with the Marine’s march…It’s a ritual. I remember one of my idols my heroes in filmmaking, he is a French director called Jean Pierre Melville. He said that “Le cinéma est mon religion”. I always say that I was born, symbolically (this is a comic relief), between a church on the right and a movie theatre o the left. And these are the two main influences in my life (laugh).If I wasn’t a film director I could be a priest. Scorsese studied to be a catholic priest before …he studied for some time to become a priest and then…

So, Éric Rouleau, this is a very important journalist. He began as a journalist and he worked for the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and he came and met Nasser and he said in his book a fact that we all knew that, Nassser didn’t go to bed unless he watched a Western, an American Western every night. This book came out translated six months ago in Al-Ahram newspaper but they stopped after the fourth episode, I don’t know why but it was very interesting. That was when Nasser tried, after 67, to approach Charle De Gaulle and he urged Heykal to contact Rouleau and make an interview with Nasser and have a message to De Gaulle.

Well, so till the early sixties, no clear involvement of the state in film industry, and all the films that reflected some of the principles and the issues of the revolution were adopted by the filmmakers themselves with no arbitrary or dictation from the Authorities. That’s what I would like to stress.

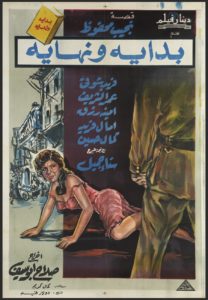

Things changed after the nationalization. Now the state was almost the sole and biggest producer of the films and actually it was run by people who were in a way of the left wing. So those people adopted social realism as a static attitude with its political implications. In this period the films that had a strong social and political statement had the priority in production and because the government had to support or to make jobs available they made a category called ‘B pictures’ not as the ‘B pictures’ in Hollywood. The ‘B pictures’ were films with smaller budgets, so not the big names of directors or photographers (could) find jobs because there was no private sector at that time; it was very weak. So they made this category “A pictures” and “B pictures”. Most of “B pictures” were commercial routine films, but the “A pictures” were adaptations of literary work, most of them and that was a step. Of course there were films based on fiction before like ‘Rodda Qalbi’ like (…) like ‘Bedaya wa Nehaya’ (The Beginning and the End), all these films were based on very well-known literary works but after the nationalization that was a conscious trend, to adapt literary works to the cinema.

In this period, now I am talking as a scholar. In my master I noticed that when I was analysing films, in some films, in a way of flattering or kissing the government ass they put some incident, which is historically not correct in order to promote the ideas of this period, specially the socialism.

Of course this lasted until 1970 when Nasser died and the nationalization disappeared and the industry became a private enterprise as it was before. But, to be objective, some of the best Egyptian films were produced in this period.

Rosa: For example the price that the people had to pay to go to the cinema was a reasonable one? So cheap that anyone could attend? And to what extent did cinema influenced the Egyptian people back in the day?

Samir: Well, before television cinema was the cheapest entertainment. No television, only broadcasting and the cinemas were all over the country. In Egypt, it was the lowest price ticket, few piastres. Personally, I have three tickets. It is very rare on a theatre ticket to have the same ad of the film printed on the ticket. It happened three times and I have these three tickets; “EL Nasser Salah El Din”, “The longest day” (…) on the invasion of the Allies in Normandie. The ad was the helmet of a soldier on the beach, and the third one was Lawrence of Arabia. The price was very low. Of course, I went to the cinemas on Fridays morning, the cheapest and it was from 10 to 14 piastres, peanuts. And this was a first-class film theatre. In the local districts, the highest ticket was ten piastres, seven and a half piastres…I am talking about the sixties and the seventies. So, cinema as it started was the most democratic, the most popular means of entertainment for the poor people, for the masses.

Rosa: And how were the films announced?

Samir: First of all, the ads were put in front of the theatres and in the streets. In the streets there were fixed places for the ads. In local districts there were also fixed places, where the one-folio ad used to be put in the streets. Some theatres were using some popular ways of promotion. I mean a tricycle, or a car driven by a monkey , carrying banners on both sides with the ads of the film and they walked in the streets announcing the film, as when a circus comes to town; It’s the same. But when the television came, all the trailers of the films were shown on television in its original length. Of course they weren’t aware of the potential commerciality, so the trailers were shown its full length. Now if you can get 30 seconds it’s ok because it is very expensive. In the early sixties when the television was new trailers were shown in their original length; that was an additional way of promotion of films.

Rosa: Were there usually adverts and reviews of the films in the newspapers?

Samir: There were ads every week, at the beginning of the week. It used to be on Mondays and now it is on Wednesdays. Every Monday or Wednesday the new films, foreign or Arabic they had their ads on the newspapers. And of course for the reviews there were specialized magazines; El Kawakeb, for example. I was an addict to El Kawakeb. I have some reviews of the Nuremberg Trials, of Marlon Brando (…) some articles talking of the new generation of directors (…) I am a collector I have very old magazines and newspapers so when I tell you that the prominent figure in the 52 Revolution was Jefferson Caffrey, the American Ambassador in his white suit visiting all the locations with the Revolution officers. Nobody knows that but I have the newspapers and the magazines.

Rosa: And what about the censorship?

Samir: Censorship was first a section of the Ministry of Interior, and then it passed to be a section of the Ministry of Culture and Guidance. It is very strange with the censorship because it always depends on who is the head, who is in charge. If it is a cultured man then there is a margin of liberty if it was just an employee, a bureaucratic one then all the art suffers a lot. So it always depends on who is in charge. Of course politics was the main taboo. It could even tolerate sex but when it came first to politics second to religion, no.

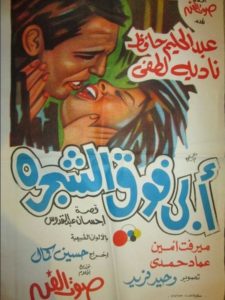

Rosa: I remembered reading that there was this film in which the audience would count the kisses.

Samir: Yes, exactly. Abdel Halem Hafez in “My father on the tree” (Baba fawq el shagara). People were counting kisses in the cinema theatres: “Tweenty, twenty one!” Well, when you see the films of this period, the late sixties and the early seventies, in comparison to films of nowadays they are pornographic. (…)

In the 51, a fanatic, not fanatic but by that time he was a fundamentalist, he was a star, a producer and director, his name was Hussein Sedki he used to be in musicals and all that but he was a fundamentalist, a fanatic, very conservative. He made a film called “Sheikh Hassan”. It was a clear attack on Christianity and how a sheikh affected a Christian girl to become a Muslim. The censorship at that time felt that it will propel a lot of protest and they banned this film. He had to re-edit it and re-shoot some scenes and it was later screened with another title “Leilat el Ader” (a sacred night of Ramadan) but first it was called “Sheikh Hassan” this is the only one obvious interference of the censorship in a religious matter but mainly it was political.

Rosa: What I read that struck me is that the rules of censorship were the same during the King and afterwards, they didn’t change. They just were applied differently.

Samir: You could ban a film if it was dangerous to the principles of the society, ok? The principles of the society under the King’s rule or the principles of the society under Nasser’s rule. They are very abstract rules than can apply to any regime at any time, according to who is in charge, according to who interprets these rules.

When the censors fear something they divert to upper authorities in order not to have responsibility, so the authorities watch this film and that happened in two very well known cases: “Shey men el Khauf” and “Miramar”. In “Shey men el Khauf” they felt that it was a metaphor for Nasser Regime and they showed the film to Nasser and they say that when he saw the film he said: “If people think that we are that gang, they are right; we should be executed” and he released the film. He felt it was an insult, how people can see us as this gang.

Renaissance of the Egyptian culture carried out by the ex-army officer and later Minister of Culture Sarwat Okasha, he made a magnificent contribution to the cultural movement in Egypt by establishing or founding the film institute, the conservatoire, the ballet institute and improving the already existing Theatre Arts institute and the movement of translation. It was a real Renaissance. There was a very strange thing; the government: a military one, but the culture was left-loose, for the advanced and the free thinkers and even the communists and socialists who were prisoners under the regime of Nasser they were his supporters. They were released from prison to assist his regime, as opposed to the Muslim Brothers who came out with a desire for revenge.

Sarwat Okasha he studied in France, he made excellent translations of the renaissance and the arts and the writings of the renaissance in Italy, important books on Egypt in the eyes of the foreigners and illustrations. He was an institution in himself this man, Sarwat Okasha.

One of my ambitions when I was a student was to make a re-evaluation of the Egyptian Cinema, a huge critical study to re-evaluate the Egyptian films benefiting from the new author’s theory from all these studies but that meant that I wouldn’t direct films. So I took only the chance of the masters, because this is a critical essay, to analyse Egyptian action films. But it was a dream for me to make a re-evaluation of Egyptian Cinema to give directors who were neglected and under estimated their real value and to demystify icon cults (clasts) directors who were pumped by advertising and overrated but I had to make films because that was the first thing that I wanted to do. (…) It is very interesting because until the late 1950´s you cannot differentiate technically between Egyptian, American, Italian and French films, technically. The gap started in the 60’s: the style, the techniques, the acting…you cannot differentiate. And some of the people who became international figures, started up in Egypt. For example: Mihalis Kakogiannis.

Rosa: What I read as well about the nationalization of the film industry is that of course it was a decision of the regime but it also came as an initiative of the private filmmakers because they were not earning as much money because they were depending a lot on foreign funders, so maybe it was a critical point and they agreed easily with the government’s decision of nationalization of the industry.

Samir: there was no objection at all. They agreed easily. Since they give me the money to make films it’s ok. Whether you are the government, whether you are the devil himself, just give me the money and I will make the films and I will sneak my way. Of course we have some gossips, for example; the head of the second company: Gamal el Lessy. This is a government- run company, so this is not my money, so I can give you bigger salaries, but in return of giving you a big salary here you go to my brother’s private company and make films for less money, ok? And that is how El Lesy made his company, his empire. ‘Behind every great fortune, there is always a crime’. It was a quotation in the Grandfather, said by Honoré de Balzac. Of course, in every state-run institution, corruption prevails. It has its good effects, but of course it has its bad by-products. (…) Le cinéma é mon religion.

[1] The song that Samir Seif hummed for us was ‘Stripes and stars forever’, a patriotic American march widely considered to be the magnum opus of the composer John Philip Sousa. It is the official National March of the United States of America.