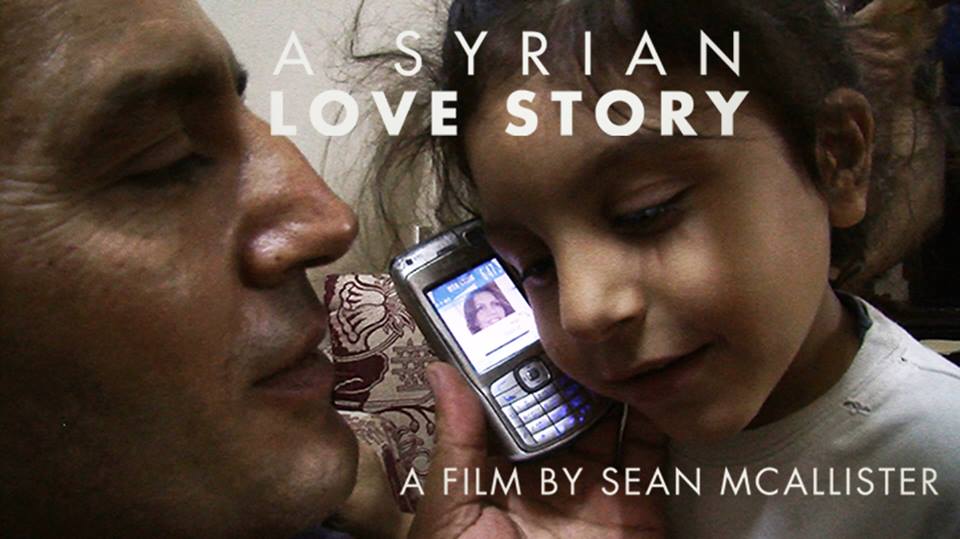

It was a privilege for Caabu to host a screening of A Syrian Love Story in Parliament. Here are some of my thoughts on why this documentary should be a must see for anybody, but also why witnessing one Syrian family’s struggle is also a reminder of our collective failure.

With over 4.1 million registered Syrian refugees, 6.5 million internally displaced inside Syria (these two figures combined amounting to half of the country’s pre-war population now having fled), and 13.5 million people in need of humanitarian assistance, it is a struggle to extract the personal from a conflict of such depressing statistics. The figures are so grave and so overwhelming, that the individuals that make up each single digit are all too often forgotten.

A Syrian Love Story is not only the focus of one family’s breakdown and reconfiguration as the country crumbles, but also a reminder that every single person and community affected and part of the statistics above, has such a story to tell. In the very worst cases, Syrians that make up that 4.1 million refugee population, can recount death, siege, torture, rape, yet all of them have been subjected to displacement and being away from home – by whatever means that came about.

It is in light of such figures where documentaries such as A Syrian Love Story ought to have their moment, and be as publicly accessible to all those who have a deep sense of moral outrage about what is happening in Syria, and especially to those who have yet to really comprehend and relate to the extent of this crisis. Of course, we wish that a documentary detailing the journey of one family from Syria in 2010 to Syrian refugees today, was one that should never have had to be made.

A Syrian Love Story was screened in British cinemas and arrived on our TV screens in the weeks after the body of a three-year-old Syrian boy, Aylan Kurdi, had been washed up on a Turkish beach in early September 2015 – incidentally, over 70 children have died trying to reach Greece since Aylan’s death. Certain images have led the way in which we have responded to this crisis. Aylan Kurdi reignited a debate about a refugee crisis that had been overlooked. This image, of a boy, part of a family trying to reach Europe, dead on a beach where British tourists have long frequented, and dead in a climate where Syrian refugees were being as rapidly dehumanised as the number increased.

There were those voices that were screaming, including the Syrian voices we neglect, “why are you only caring now? Where have you been” as the number of Syrian refugees rapidly increased, from 200,000 people in September 2012, to 1.8 million people in September 2013, to 2.9 million people in September 2014, and over 4.1 million people today. Many would argue that inaction over the refugee crisis meant that Aylan Kurdi was already dead in 2012.

This phenomenal documentary charts the journey of Amer and Raghda and their sons Shadi, Kaka and Bob. We first meet them through Sean McAllister in 2010, a chance meeting at a Damascus bar where Amer, a Palestinian freedom fighter talks about his Syrian revolutionary wife Raghda, who was then imprisoned by the Assad regime. It begins as a story of a husband missing his wife, a fight for her release and a family needing their mum back. One of the most distressing scenes is that of Bob, the youngest son, crying for his mum to come home. But as the conflict begins and plays out in Syria, key moments of the crisis such as the murder of 13-year-old Hamza Al Khateeb in Daraa and the siege on Yarmouk Palestinian camp, intertwine with the family’s own breakdown and personal devastation as a result of this war. You hear an appalled Kaka whose voice has not yet broken shout, “they cut his dick off’, when hearing about Hamza Al Khateeb in the early stages of the crisis, when the family is still in Damascus.

Throughout the film you witness the crisis in Syria as it continues to play out, and you are with Kaka as his voices breaks and becomes an incredibly mature young man in Lebanon and later in France. His teenage years have been drastically altered by this crisis. We see Yarmouk when a very young Bob is playing there in 2011, but later see the images of siege and devastation, and Facebook photo albums where a person can just go through the photos and say which of their friends are dead – in this case, the majority, many of which succumbed to starvation. The crisis may begin in Syria, but A Syrian Love Story is the visualisation of a crisis that extends geographically, first to Lebanon, and then to France, but also extends to every aspect of one family’s life.

A Syrian Love Story draws out the tensions that so many Syrians are having to face about how they deal with the conflict. The physical and psychological effects that being away from Syria has upon Raghda are obvious, as is her guilt about not being there. On the other hand, there are those who need to keep their distance from the ‘revolution’ and from the conflict, like Amer, in order to stand any chance of being able to rebuild and adjust to the situations they now find themselves in.

All too often, the images we see of refugees are of hopelessness and destitution, of victims and of poverty, or we hear the negative framing of the refugee crisis, with people labelled as “swarms” and “marauding”, or portrayed as chancers, opportunists and scroungers. In the majority of such labels, individual lives are removed. ‘Syrian’ has become synonymous with ‘refugee’ or ‘migrant’ and ‘refugee’ is all too often synonymous with destitute and helpless, and to many ‘migrant’ is void of any sympathy or compassion. It is through the framing of this conflict that our judgment of Syrian refugees is impaired.

It would be unfair to Sean McAllister and A Syrian Love Story to say that the main purpose of this documentary was to challenge the discussion that we have about refugees, about migration, and about the conflict in Syria. The documentary has evolved with the discussion, and has a significant role to play in re-assessing how we look at those who are subjected to this crisis and all the repercussions of it. It is wrong to see Amer and Raghda as hopeless victims. The rawness of their relationship, their family set up, their abilities as parents, their life as refugees, and their flaws and imperfections are laid bare. They are not caricatures, nor are they stereotypes of what a refugee ought to be, but challenge the notions of what it means to be displaced, in emotional and political turmoil, and to keep functioning in some way as a family. Amer and Raghda do not demand our pity, nor does A Syrian Love Story demand that we do pity them. Nor should we, and this is one of the most superb elements of this film.

The viewer is present in the anger, the upset, the attempted suicide, and throughout the breakdown of a family. Nobody wants to be a witness to this and although we may not be able to relate to every single component, there feels a strange sense of privilege in being able to become part of their family. This is despite the genuine concern and unease at watching a family endure some of its worst moments. Much has been said of Sean McAllister’s style, with questions asked if he is intrusive, and if he bears some kind of responsibility for their situation, given that the family had to flee Syria when he himself was arrested by the Assad regime. His relationship with Amer, Raghda and the boys is extraordinary, and it is his approach that is the enabler for this documentary to challenge how we relate to the refugee crisis through being with just a few individuals.

At Caabu, we screened A Syrian Love Story to members of the House of Commons and House of Lords in Parliament. The appeal to them, and the importance of British politicians watching this film, is equally as important as it is to those who will not be watching it with a political interest. McAllister himself says that his documentaries are there to appeal to the groups of men drinking in the pubs of his native Hull, as much as anyone else. You may finish watching A Syrian Love Story with the feeling that you have smoked a couple of packets of cigarettes and drank a few bottles of wine with Amer and Raghda, or that you may feel the need to, but if this documentary has had the ability to motivate just one person about this awful crisis, then the impact is far more than 76 minutes, and one which it should be commended for.

Joseph Willits has been Caabu’s (Council for Arab-British Understanding) Parliamentary and Events Officer since March 2013. At Caabu, Joseph has led cross-party Parliamentary delegations to Jordan, Lebanon and Palestine, and has spoken to schools about Islamophobia, Arab and Muslim stereotypes, multiculturalism and the situation in Syria, as part of Caabu’s education programme. He tweets @josephwillits.