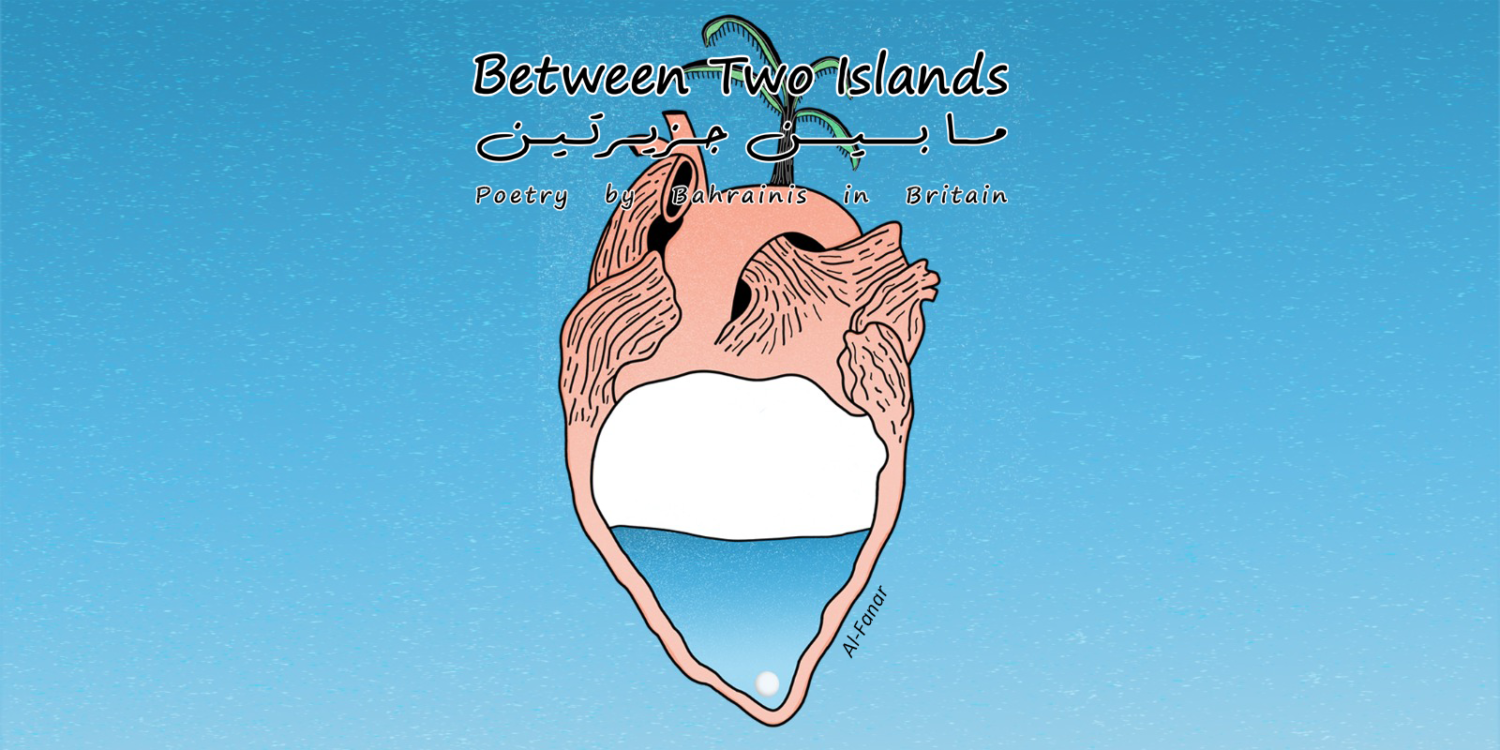

Between Two Islands, edited by writer and poet Ali Al-Jamri, is a multilingual poetry anthology showcasing the talent of the UK’s Bahraini community. Over a series of online workshops, thirteen Bahrainis living in the UK gathered each week to express their unique diaspora community experience and learnt how to read and write poetry. Together, they explored diaspora, duality, resistance and yearning, and as a result, a poetry zine was produced.

It is the first anthology of its kind for the community. Projects and Communications Assistant Reem Hammoud took up the opportunity to ask Ali why.

1. What were the motivations behind putting together the workshops and to present it in a zine?

I knew for a long time that I wanted to produce poetry in 2021. It is now a decade since the Arab uprisings, and I wanted to mark that in some way. I was 19 and the uprisings and revolutions had a huge impact on me, and I first turned to poetry as a means of working through my emotional responses. Bahrain in 2011 saw the largest protest movement in proportion to its population anywhere in the Arab world, and the crackdown that followed has torn apart lives and reshaped the contours of Bahraini society. We still live in the shadow of that traumatic year, but without freedom of expression, it’s not something Bahrainis can express except in the vaguest terms. Ten years on, there is an entire spectrum of lived experiences in the Gulf that are overlooked because they do not fit into the preferred, glitzy narrative.

I originally had the idea of self-publishing my own anthology of poetry about the past decade. But I felt a lot of pressure, as I think a lot of marginalised people do in the West, to ‘represent’ my people. I talk about this in the introduction to the anthology. At some point I had this idea, what if we brought Bahrainis together to write poetry? Because I can’t be the only one facing these questions. So the project transformed into conducting poetry workshops with other Bahrainis in the diaspora. At one stage in the planning, I completely ditched the idea of publishing anything, but I’m grateful to my mentors who suggested I incorporate a zine into the project. Once we were in full flow with the workshops – we discovered we had so much to celebrate, and participants were keen to put their work in the zine. That ended up being the Between Two Islands anthology.

2. You mention that this poetry zine is ‘the first communal expression of a Bahraini diaspora identity’ (p. 1) in Britain – how did you identify this gap in literature and/or more generally, and why do you think this is?

Britain probably has the largest Bahraini population outside of the SWANA region. There’s likely no more than 10,000 of us in the UK (and 5 digits is a generous estimate). But in our context, that’s a large amount – Bahrain has a tiny population, 1.3 million in the last census.

Bahraini experiences in the UK are very varied, but there is a small community where I grew up in London, which includes a lot of political exiles and refugees as well as other migrants. And it includes their children who’ve become British as well as Bahraini. A large proportion of these families come from what we’d call working and lower middle-class backgrounds, so again they’re not your typical picture of the Gulf. Bahrain has a lot of diverse communities, but this one is mine, and our experiences aren’t reflected in your usual array of Arab arts in the UK.

I identified this gap simply by never finding a complete reflection of myself in any of the art and culture I was consuming. Some came close and made powerful impacts – I think of films like The Nile Hilton Incident (2017) and Iraqi exile poets like Fawzi Karim and Amal Al-Jubouri. There is also more literature coming out of the Gulf and into translation in the West, like Celestial Bodies by Jokha Alharthi (Oman) and The Corsair by Abdulaziz Al-Mahmoud (Qatar). But nothing that I felt spoke directly to my experiences.

Most Bahrainis who settle in the UK have the same things to prove that other migrants do. We have a lot of highly educated doctors, engineers, economists and tech people as a result, but not many artists. But if you talk to Bahrainis, art and poetry are often quite close to our hearts, for example in Ashura elegies, or love for Palestinian poetry. I wanted to bring that to the surface and celebrate it.

Illustrations by Fatma Al-Fanar

3. Given that these workshops took place a year into the pandemic, do you feel that it impacted the workshops or the outcomes in any way?

I’d initially planned to hold the workshops in London, but due to the pandemic, pretty quickly I switched my plans to digital. Zoom was liberating in the sense that we had Bahrainis signing up who were in Aberdeen, Brighton, Cardiff, and all over. I was lucky to work with a great co-facilitator in Liverpool, Amina Atiq who’s a Yemeni Scouse poet, and we made the best of the digital situation. For example, with the help of my mum in Bahrain, I organised a care package full of goodies to be sent to all the participants, which they weren’t allowed to open until we were all on Zoom together. Everyone came to the session excited, and we wrote poems around the gifts. These workshops helped give us meaningful connections in a very isolating time.

One of the cleverest poems in the anthology is Legacy Hands, by Fatema Abuidrees. “Legacy hand” is the term for when someone forgets to put their hand down after asking a question on Zoom or Teams – they might accidentally keep their hand up for the rest of the call. And our Bahraini legacy as a diaspora was a big topic in the workshops. This is a great poem which blends the idea of a “legacy hand linger[ing]” on Zoom with the “quest for legacy” we embarked on – also on Zoom.

Gift hamper sent to each participant

4. Can you tell us a little bit about the process itself, what was it like for the Bahraini participants to meet each other and express themselves about both islands?

We’d planned the workshops around ideas of identity, and to conceptualise that we had 5 themed workshops. These themes, in order, were “Heritage & Inheritance”, “Love & Conflict”, “Am I British?” “What Remains?” and “The Future”. I wanted to encourage us to think in Arabic, even though a lot of us were more comfortable in English. In the first half of the workshops, we’d look at Arabic poetry with English translations, and in the second half we’d do writing exercises. Participants were encouraged to engage in the language they preferred. This took us through a journey of our identities. In the first workshop, we read a Bahraini folk poem and Palestinian poetry yearning for a just return to the land. And in the final workshop, we did a visualisation exercise where we imagined visiting an abandoned, underwater Bahrain. Our country is very fragile to the effects of rising sea levels and climate catastrophe. The idea that Bahrain might not be there in the future is a real one, which is why I included the visualisation exercise in the anthology. One of the Arabic poems in the anthology, قاربي يستقرب الماضي مجالا (“My Boat Approaches the Past”) by Mohamed Arab was written in response to the exercise.

We had 13 participants aged between 16 and 50, mostly women. Many of us knew each other already, even if only by reputation – Bahrain being so small – but we got on very well. It was a safe space. Everyone had their own story and many had suffered crises and traumas in the past which the creative process helped them engage with. No one judged anyone else’s lived experience; no one was made to feel ‘inauthentic’ or judged on how good their Arabic or English was. We celebrated and encouraged each other. Some of the poets most resistant to poetry turned out to be the most talented amongst us.

One joyous thing is that we express a lot of common ideas. For example, Taher Adel’s These Seas features “a reincarnated pearl diver” who joins “the opera of the lost”. Mohamed Arab’s diver encounters ghosts who tell him “تحفظنا في قلبك أغنية” – “We are in the songs in your heart.” The poets of Buying a ticket and Two Islands both find themselves pulled between the east and west. Trees appear in at least five poems, always alongside ideas of safety and belonging, while the sea is an ambiguous danger. This emerged naturally, reflecting that we were tapping into a shared imagination held deep in our psyches.

Bahraini coffee alongside cultural items

5. The sense of a strong organized Bahraini community can be felt throughout the zine, will there be any future developments with this project?

The participants want to continue building on this shared experience. Right now, we’re looking at ways to keep this community group going and open it for more people to be involved. I’ve received messages from Bahrainis in the UK and beyond saying they’ve felt a connection to the anthology, which I’m thrilled by. I’m also looking at ways to continue building the links between the Bahraini and other migrant and racialised communities in the UK through arts.

There’s a couple immediate follow-ups I have in mind. I’m working on a soundscape as a final element of Between Two Islands, and I have further thoughts to explore the symbols and imagery expressed in the anthology. I’m also beginning a new translation project focused on Bahraini poetry, and I’m committed to this community-led approach to my art practice – so in some ways, I think it will be a continuation of Between Two Islands.

Between Two Islands: Poetry by Bahrainis in Britain, ed. Ali Al-Jamri. Published by No Disclaimers, supported by Arts Council England.

To read the digital edition or order a printed copy: https://alialjamri.com/betweentwoislands/