PERSONAL ENCOUNTER WITH THE CINEMA CRITIC AND SCRIPTWRITER:

RAFIK EL SABAN

18th July 2013, Cairo, Egypt.

“The sweet voice of this 81 year-old man was enveloping and took us through a fascinating trip of knowledge and experience to the golden era of Egyptian cinema. I wish you had not left us so early, Rafik, so you could read the dissertation you so much helped me with. Anyway, this is for you.” – Rosa Perez.

Rafik El Saban (1931 – 2013) was a Syrian author, screenwriter and film critic who had lived in Cairo from the 1970s. After relocating to Cairo, Rafik wrote the screenplay for the film Zaer Al Fajr (A Visitor at Dawn) in 1972. Thereafter Rafik’s association with Egyptian cinema began. Amongst his best known titles are Al Ekhwa Al A’adah (Brothers in Conflict), Qitaa a’la Al Nar and Layla Sakhina. Aside from his screenwriting, Rafik was also a revered film critic whose opinion was held in high esteem across the Arab World. He passed away after an illness on 17 August 2013.

Rafik El Saban (1931 – 2013) was a Syrian author, screenwriter and film critic who had lived in Cairo from the 1970s. After relocating to Cairo, Rafik wrote the screenplay for the film Zaer Al Fajr (A Visitor at Dawn) in 1972. Thereafter Rafik’s association with Egyptian cinema began. Amongst his best known titles are Al Ekhwa Al A’adah (Brothers in Conflict), Qitaa a’la Al Nar and Layla Sakhina. Aside from his screenwriting, Rafik was also a revered film critic whose opinion was held in high esteem across the Arab World. He passed away after an illness on 17 August 2013.

Rosa Pérez, MA student of Middle Eastern Studies at SOAS (2012-2013), went back to Cairo in July 2013 to do some research for her MA dissertation: “Nasserism on the Silver Screen. The use of cinema as a propaganda tool under Nasser’s Egypt”. She used the opportunity to visit Rafik El Saban in Cairo and interview him about the period from the 50s to the 70s – 80s in Egyptian Cinema and the nationalization of culture. Below are excerpts from that meeting.

(Translation of the original interview in Arabic)

The point of view that can be made about that period, the Nasser period, you cannot consider it strictly from a development point of view. The policy in the field of art is very different in this period. The period of Abdel Nasser was a very revolutionary time. The application of committed art that benefits the country was not like in the Soviet Union case. When Abdel Nasser decided on the nationalization of culture, the first thing he did was creating the Ministry of Culture, which did not exist before. That is already a nationalization of the thought. (You know how every story has a positive and a negative side) The positive part is that he chose a minister who had a very high level of both Arab and foreign culture, Dr Zharawat Okasha, and this gave him main livre, full freedom to do what he pleased. The first thing he established was the Academy of Arts, on the basis that he believes that the art has to be based on a scientific foundation. The Academy of Arts combines the High Cinema Institute, the Theatre Institute, ballet, conservatoire, popular arts and Arabic music.

Here all the arts are under the Ministry of Culture and so the minister of culture can create a cultural consciousness and this matter has two sides. The negative side is if the ministry falls under the hands of a person who is culturally unaware like what happened in the Soviet Union, someone who does not appreciate the importance of culture, it can destroy the culture.

Nasser and the Minister of Culture decided that just like we created the Academy of Arts and the conservatoire we had to do a public division that will create movies in addition to the private sector, which only promotes movies that are commercial.

You have two branches: the private sector is free to do what they want while the State has to control the balance between the public and private by creating movies in the public sector of high level with high artistic expression (script writing) and by opening the field to young artists who can present their artistic potential. This is how you control the commerce and the art. This of course was a very ambitious project that the public sector was able to achieve. On the other end, I do not want to talk about the failures of the public sector. There were too many interference in management that led to thefts, so this beautiful idea that Nasser had, in terms of a balance between public and private sector did not work out due to the thefts etc. And then Abdel Nasser passed away and Sadat came and it stopped the public sector because of the financial disasters involved and the corruption and the thefts. However, (with emphasis on however) public sector presented during its time movies that the private sector would have never created.

Firstly, the public sector movies were often based on literary works and they chose big authors in literature such as: Naguib Mahfouz, Ihsan Abdel Qudoos, Yussef Idris, and presented movies which are now considered treasures of the Egyptian cinema. They got big directors and opened the space for some of the young artistic Egyptian directors like Ashraf Fahmy, Dawod Abdel Sayyed, and many others like Khayri Beshara and Ahmad Khan. They all were given an opportunity by the public sector. And all of these movies are considered classics of the period from the sixties to the eighties. The movies produced in this period are considered the main heritage that Egyptian cinema currently depends on.

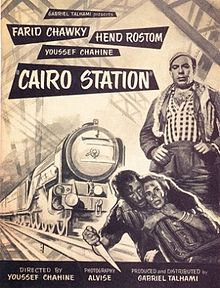

If we ask what the Egyptian cinema produced? We will say: Haram, El Mommia (image on left), El Bustagy, Shay men el Khauf, all of these are movies financed by the public sector. Without the support of Public Sector Ashraf Fahmy, Salah Abu Seif would not have made movies like El Adeyya, Qahera 30, even Youssef Chahine, the public sector worked with Assia in the production of El Nasser Salah Eddin. Although the public sector did not finance it completely but contributed to the completion of Nasser Salah Eddin and presented Youssef Chahine the opportunity to create El Nas we El Nil … The public sector with all its negative aspects, left us with a very important heritage to the Egyptian cinema. So whenever the period between the 60’s to the 80’s is considered you will always go back to the movies created by the public sector. Even Ramsis Naguib who was the master of the private sector and made very important movies in the private sector, started his career in the public sector and was trained by the public sector until he became independent with his own productions where he was trying to achieve a balance between the commercial and the creative arts. He was convinced that what becomes historical cinema is the artistic side not the commercial (it can provide a lot of money but without an artistic aspect it will be forgotten with time).

If we ask what the Egyptian cinema produced? We will say: Haram, El Mommia (image on left), El Bustagy, Shay men el Khauf, all of these are movies financed by the public sector. Without the support of Public Sector Ashraf Fahmy, Salah Abu Seif would not have made movies like El Adeyya, Qahera 30, even Youssef Chahine, the public sector worked with Assia in the production of El Nasser Salah Eddin. Although the public sector did not finance it completely but contributed to the completion of Nasser Salah Eddin and presented Youssef Chahine the opportunity to create El Nas we El Nil … The public sector with all its negative aspects, left us with a very important heritage to the Egyptian cinema. So whenever the period between the 60’s to the 80’s is considered you will always go back to the movies created by the public sector. Even Ramsis Naguib who was the master of the private sector and made very important movies in the private sector, started his career in the public sector and was trained by the public sector until he became independent with his own productions where he was trying to achieve a balance between the commercial and the creative arts. He was convinced that what becomes historical cinema is the artistic side not the commercial (it can provide a lot of money but without an artistic aspect it will be forgotten with time).

A lot of movies make a lot of money but are not remembered and others which do not make money but remain iconic such as Bab el Hadid and El Bustagy, El Mustahel and El Mummia, those are the ones which remain in our memories and stood the taste of time. El Mommia did not make any money in its first appearance and it stayed only one week in the cinema. However, it is one of the few Egyptian movies recognised by the international encyclopaedias. All of Shady Abdel Salam movies were produced by the public sector.

The downfall of the public sector was administrative and not artistic. Abdel Nasser and his regime when they started off the public sector along with the private sector, was for a future vision of extreme realization, but they did not know that this would not be achieved because of the incompetent people who tore it apart from the inside.

The Egyptian experience had a lot of positive aspects. The people who oppose Abdel Nasser always criticises the public sector and considers it to be a dark period in the history of Egyptian cinema but I am against this. I think it was an enlightening period and without what the public sector produced there would not be Egyptian cinema today. Egyptian cinema was only about Ismail Yassine movies and the public sector came in and reshuffled the whole industry. It lost a lot of money because of all the thefts carried out by the administration not by the directors (corruption…). However, if the public sector was managed as Sarwat Okasha had in mind it would have been managed much better and would have continued until today giving us movies and art. Now the young people who are starting today they have to compromise a lot, they have to sell. (…)

My own personal experience, I made one film with the public sector and it became famous and Ramsis Naguib came and contracted me for three films directly after, just from one movie. He was the biggest private producer. Now we do not have a Ramis Naguib, we have Sobky with sexy and cheap dialogues. (…) The hope lies in the young generation who will rebel against all this” jungle rules” imposed by the commercial cinema dealers.

The 50’s, 60’s, 70’s (public sector era) no matter what is said was the golden era of Egyptian cinema and the age of prosperity for Egyptian cinema. All the big movies now that have recognition in the encyclopaedias are the movies done by the public sector in that period.

The influence of the 52 Revolution in movies and the propaganda:

The royal regime, especially five to seven years before the Revolution, started to feel that there was discontent in the streets and they could feel the signals that a revolution will take place because it was a very corrupt regime and the stories of the king were becoming too much, the corruption, etc. This led to extreme censorship thereby they did not allow any movies with a political twist. They did not want movies to awake the subconscious of the people. They did not want movies touching on the discontent. They wanted entertaining movies like: Foad el Mohandes and Shwuaika, Ismail Yassine, not related to literary works (this only happened after the Revolution with adaptations of Naguib Mahfouz and others). It was all about comedies and melodrama. It was not so much a cultural experience as it was just for entertainment purposes.

Harbingers happened before 52 by Kamal El Sheikh and Salah Abu Ismail who were trying to engage with the pro revolution people by producing movies not with a revolutionary background but more with a social background. Using the social background they were able to explain very smartly what was happening in Egypt. For example when Salah Abu Seif presented the film Lak youm ia Zalem based on Thérèse Raquin of Émile Zola. The social background in this work was very clear. Kamal el Sheihk made the movie Life or Death, Haya aw Mut, set up in a police environment but with a very strong social message so the big producers could feel that there was a change happening. They could feel that there is a big moment beside the entertainment films of Farid el Atrash, Umm Kulthoum, Abdel Wahab, Mohammad Fawzy and Sabah, that there are more important things coming up.

Harbingers happened before 52 by Kamal El Sheikh and Salah Abu Ismail who were trying to engage with the pro revolution people by producing movies not with a revolutionary background but more with a social background. Using the social background they were able to explain very smartly what was happening in Egypt. For example when Salah Abu Seif presented the film Lak youm ia Zalem based on Thérèse Raquin of Émile Zola. The social background in this work was very clear. Kamal el Sheihk made the movie Life or Death, Haya aw Mut, set up in a police environment but with a very strong social message so the big producers could feel that there was a change happening. They could feel that there is a big moment beside the entertainment films of Farid el Atrash, Umm Kulthoum, Abdel Wahab, Mohammad Fawzy and Sabah, that there are more important things coming up.

As soon as the revolution happened we started seeing these movies, all the stories of Naguib Mahfouz, with all what those stories entailed in terms of politics, culture, social aspects. All these movies were hiding under the sand awaiting the spark to come up, and the revolution came and ignited that spark. How come all this happened in a year? It is like a pregnant woman who does not show that she is pregnant in the first three months and then, poof!

The Arab British Centre would like to thank Rosa Perez for allowing us to sample part of her interview with Rafik for our site.