Kit Kat’s Subversive Comedy

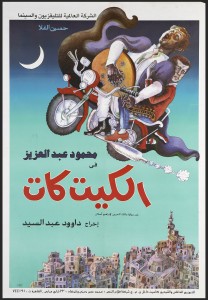

Kit Kat

Directed by Daoud Abdel Sayed

1991 | Egypt

Safar’s artistic director, the curator Omar Kholeif always envisioned the biannual film festival as one that celebrates popular Arab cinema through a critical lens. ‘I want to critique the notion of popular,’ he said, ‘and also propose what could and should be popular in the future.’ The first festival two years ago was, in his words, ‘a greatest hits’ that included classics like Watch Out for Zouzou and Youssef Chahine’s Alexandria … Why?

When Kholeif was conceiving the 2014 festival he at first thought it should have a focus on comedy. However he soon realised that ‘we’re in a darker place now. Post-Arab uprisings we were still in the process of continual negotiation and renegotiation but there was still an optimism. But with ISIS, Gaza, Egypt still in flux, Syria and Libya, the output of contemporary Arab filmmakers is not the frivolous escapism. None of the new films are comedies.’

Despite this being the case, Kholeif has always considered comedy a subversive genre in Arabic cinema, particularly in the films of Egypt’s Charlie Chaplin, Ismail Yasine, the original prints of which have been bought up and branded by Rotana, a Saudi-owned media conglomerate. Safar has always included a section of classic historic films and Kholeif felt it was time to ‘look at the past through the lens of the present to reassess some key historic moments. By revisiting this cinema, it is a way of renegotiating some of those issues and think about them differently: how the works can dialogue with each other.’

He decided to include Kit Kat (al-Kitkat) directed by Daoud Abdel Sayed, one of the most popular Egyptian films from 1991, a comedy that features a disabled main character. ‘At this particular moment, one of the things you see throughout is the emergence of a dark sense of humour pervading much of the public consciousness now. And I thought it would be appropriate to return to the 1990s and look at Kit Kat. It had just been voted the seventh best Arab film of all time and it had never been seen before in the UK.’

Kit Kat is based on the 1981 novel Malek al-Hazin (The Heron) by Ibrahim Aslan (1935–2012), a writer who according to Ahram Online ‘reflected the upward mobility of a whole class of provincially rooted writers unlikely to have emerged if not for the 1952 revolution whether they supported it or not.’ Aslan was born in a village but grew up in the alleys, cafes, houses and shop in al-Kitkat in Cairo’s poor district of Imbaba, a version of which Abdel Sayed had built on a film set.

A blind sheikh, Hosny, who plays his oud and sings, lives in a house that his relatives are intent on selling for their own financial gains. Little do they know that he has already exchanged it for a daily supply of hashish from a local dealer. The film opens with two policemen walking through the deserted nearly silent cramped al-Kitkat neighbourhood, the only sound of merriment emanating from behind a partially closed garage door where Sheikh Hosny and his friends gather, smoke hash, sing songs and generally enjoy themselves.

In Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity, the academic and film critic Viola Shafik discusses the use of the theatrical techniques of ‘structuring a plot by dialogue and monologue’ in films, which draws from Arab theatre and earlier forms of oral story-telling. In Kit Kat, the Sheikh Hosny, his son Yusuf and Yusuf’s girlfriend Saniya, among other characters, tell their life stories in verbal not visual flashbacks. Sheikh Hosny explained to his friends that he lost his sight after getting up one morning and finding a red mark on his chest. By the river, he spied a female sprite disrobing and throwing water on herself. He gazed at her so hard he lost his sight.

Shafik who will be speaking at Safar’s Saturday forum, on Saturday, 20 September, on the panel ‘Revolutionary and Revolution in Cinema: reflecting on Arab Cinematic Histories’, also considers the importance of narrative anecdotes, quotations, poems and verses, ‘nested stories within stories’ as a kind of cinematic hakawati with its roots in folk art. This device, along with ‘narrative inserts’ characterises the humorous storytelling of Kit Kat.

Just as Safar looks to the past through the lens of the present, it is the current climate of control in Egypt that greatly bothers Kit Kat’s director Abdel Sayed. He began his career making documentaries and is considered as one of Egypt’s New Realist film directors who emerged in the 1980s. He is from a generation of filmmakers who witnessed the 1967 student demonstrations and became critical of economic cronyism and corruption of President Anwar Sadat (1918–81). Last year, Abdel Sayed told Cinema Arabiata, ‘As far as I am concerned what is frightening about the current condition is [the sense of] terrorism. At the same time that I [feel it] in … [the] explosions and murders … From the other side I [am experiencing] intellectual terrorism, like McCarthyism … And this is what is frightening me, that we have found ourselves – that I have found myself – between two forces: one that wants to kill me and one that wants to silence me.’

Kit Kat is a fun film that harkens back to brighter times but its darkened overtones are applicable to where Egypt finds itself today.

– Malu Halasa

London-based journalist writer and editor Malu Halasa is our writer-in-residence. Keep your eyes peeled for her posts in the run-up and during the festival.

For more information and to book tickets, please click here.