Review by Hadeel Eltayeb.

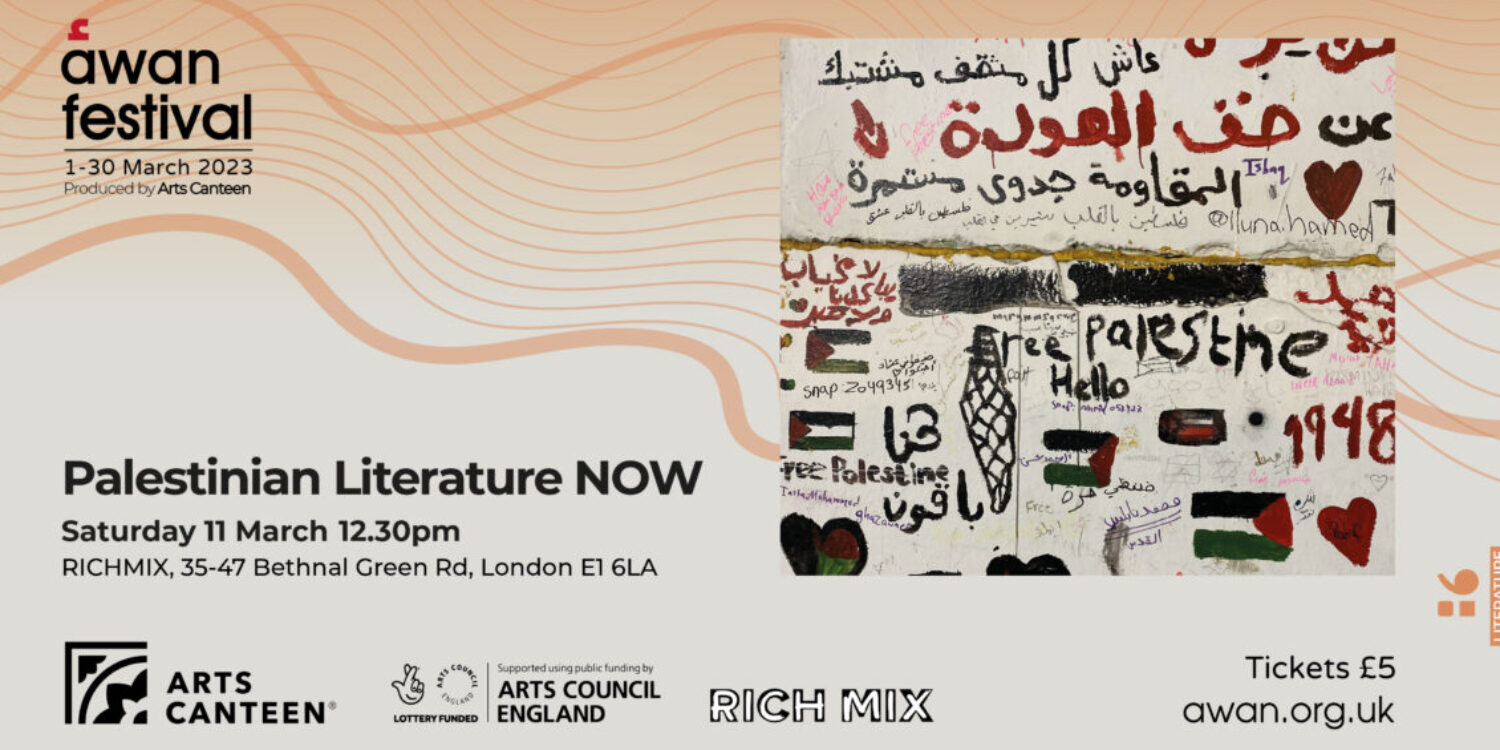

With thanks to AWAN Festival and Arts Canteen for the ticket to the event.

The event took place on 11 March 2023 at Rich Mix in London.

[19 minute read]

“The world of words that is important creates different worlds; we have to share some connection despite our differences. The ideological differences mask that sameness. We can uncover that through writing.”

On Saturday 11th March, a small audience at Rich Mix saw a discussion where the jumping off point in situating discussions of Palestinian literature in the contemporaneous moment was breaking from pasts, to focus on presents. At AWAN festival: Palestinian Literature Now, to define the present for the panellists was not a question of what but exploring whose present, reframing the discourse of literature in an awareness of contemporary fiction and self-representation. They discussed how possible it is to do this, setting discussions apart from iconic Palestinian writers from the 60s-70s, apart from the Global North, apart from trauma. It felt important that all of the panellists came together from different representations of Palestinian identity to navigate this complex discussion in this open forum.

The panellists were Shada Shahin, contemporary literature PHD student at the University of Birmingham; Selma Debbagh, writer of Out of It, editor of We Wrote in Symbols: Love and Lust by Arab Women Writers and a lawyer for the International Centre for Justice for Palestinians (ICJP); Heba Alhayek, writer and author of Sambac Beneath Unlikely Skies. The lively discussion was moderated by Nora E. Parr, a researcher who has published extensively on Palestinian literature, intertextuality in Arabic works and trauma theory (and who also happens to be Shada’s PHD supervisor).

I first came upon panellist Selma Debbagh, through her short story ‘Sleep it off, Dr. Schott” in sci-fi anthology Palestine + 100. To briefly allude to the plot, the protagonists’ histories in a future Palestine are included in the written transcript based on state records, but their own thoughts, memories and emotions are flattened in the written recording, which is all that exists of their encounters. Even when they are speaking for themselves, their input is partial and incomplete, edited and annotated within the transcript. To use sci-fi as an analogy to talk about trauma is to talk about things that require metaphor; the use of the surreal means using abstract phenomena to talk about what is usually unspeakable. The motifs of state control and data collection placed the subjects under scrutiny and created an environment totally in conflict with the veneer of utopian order. I was reminded of the short story when, of the many themes of Saturday’s panel talk, Selma brought an interesting meditation on propaganda and resistance through language; if you write about Palestine, she explained, this allegation of writing propaganda follows you and goes from what you have written about, to the editorial process, to where the funding comes from etc. She explored how Palestinian writers are constantly discredited and therefore forced to take on the role of unreliable narrator, they are forced to prove credibility out of habit. An audience member likens this to a trauma response, where when subjects are afraid of being misunderstood, they have a tendency to overexplain.

Trauma and the reading of Palestinian narratives through trauma theory, particularly by foreign critics, is a recurring theme taken up by panelists. In one sense, it is due to representations of Palestine written by foreigners (that is to say, non-Palestinians writing about Palestine) in the literature space and their body of references, in the way certain forms of time are interpreted as archive: historical time, generational time, times of loss. Shada problematizes the use of ‘trauma theory’ and how people use it to read Palestinian literature from a trauma perspective. To do this ‘properly’, she states, would require the analytical and critical space to work it through from a distance; but this is not possible because it is an ongoing trauma occurring on sometimes a daily basis. Shada was born during the first intifada, and the literature she is interested in stratified Palestinian identity post- and pre-Oslo Accords. As a literature student, she stated the connection with what they had to read and the stories of the past, which were so different from the present. They engaged with the ideal of Palestine as a kind of paradise, pre-Nakba. Shada’s interest in psychoanalysis developed alongside literature, although she describes it as “a Western way of looking at things”. She references Lara Sheehi’s Psychoanalysis under Occupation as a seminal text. Shada wanted to turn it on its head, what can Palestinians offer Psychoanalysis? She wanted to combine her passion for psychology with literature.

With Jacques Lacan and Slavoj Zizek, she saw that feeling of fragmentation that accompanied her all the time. Then when she started teaching at Palestinian Literature at Bethlehem University, there was also resistance to reading new authors. She wanted to teach untranslated texts; to question what gets to be translated in the first place. She thought of it as “What do the English translators/agents want people to know about Palestine?” This is how it started for her. She knew almost every article on Palestine was written by foreigners, who would visit for a few months and then become ‘experts’ and later they become her references at university. Particularly in the field of criticism. She thought, “why can’t be it Palestinians from within Palestine writing?” She started with psychoanalysis and reading Lacan and Zizek, reading as part of a collective that she had to advocate for. There was the tension between herself as a woman, that universal aspect of being, and her as a Palestinian, a reader, a teacher. “We all have desires, dreams, hopes. It’s not always solidarity and s’mood”. She repeats importance the Arabic word, s’mood, meaning ‘steadfastness or standing tall’. It doesn’t have to be a political concept, she felt; it can be through education and through dreams but if you go back to Palestine, she says, people are happy, they go about their lives. At night there is bombing, death everywhere, but in the morning, life goes on. Shada thinks it is more about the different forms of coping that helps them live. She recalls poet Rafeef Ziadah’s words that, “we teach life.” She puts forward that Palestinians have been excluded from trauma narratives, “So how can we force our way into the mainstream narratives”?

Edward Said once referred to the “permission to narrate Palestine.” The tools that once denied Palestinians the right to narrate were once cultural and artistic tools, and the erasure once written about by writers such as Ghassan Kanafani, is a literary mantle that the panellists talk about shifting away from. Another sense of trauma that the panellists talk about needing to distance from, is who gets the permission to narrate as Palestinians and where it is more/less appropriate to do so. Heba Alhayek, who is from Gaza, notes at this point thinks the panel covers a very diverse representation of Palestinian knowledge and experience in Literature. She left Gaza for Egypt when she was 22. She had a different curriculum to the rest of the panel, although she agrees with earlier descriptions of schooling as a “dulling experience” for most. However, this changed as she was exposed to literature. Her dad was a poet, and there were bookshelves around the house, full works, that she could reference and draw from in her own work. Her access and exposure to non-translated Arabic texts informed her writing. She feels like the Palestinian discussion on who is more/less Palestinian is damaging, because they have all been uprooted. She started writing and blogging in 2007 to 2011, to write more creatively. It was a project related to the Qattan centre, who also run the Mosaic Rooms in London. She feels it was the biggest push for her as a writer today. The writing she enjoys today is one with political consciousness, not overtly political, but it is how they experience the world. She grew up on Palestinian Resistance literature, or “Adab al Maqama“, but is interested in writing that moves away from this.

Selma, who I mentioned earlier, is half English and describes a constant struggle with imposter syndrome in her youth. She went to school in Kuwait, and she had some choice words to describe her experience at an international school in the Gulf; “Sometimes she thought it was an extremely diverse environment, sometimes she thought it was a laboratory for a particular kind of racism.” Her experience of her identity was complex and she described Palestine as ” a private hurt in her household”. Her school was full of Palestinians, and in that setting she feels she didn’t self-identify as Palestinian at that time and wouldn’t have been seen as that. In her 20s, she moved to Cairo and it all changed after reading Kanafani’s novel, Men in the Sun, in which she saw her father’s experience. She carved an important space, through her writing in English, allowing for discussion about a greater collective in the political space. She was interested in language and hybridity, knowing she herself is hybrid. Her first novel, Out of It, captured the feelings around the Oslo Accords and her friends who were politically active. She wanted to reflect the nuances behind those who lived in the Gulf and had less inclination to get involved in political activism and those friends of hers from Cairo who could do and think of nothing else. She questioned, how much sacrifice would you make, under those conditions? She reflected on that in the broadness of those who considered themselves Palestinian, and the challenges associated with it.

Language and its inherent symbolism an important aspect in terms of tools, for the panellists. The way language is employed and which audiences they write for, and how this changes, is in an interesting transition. Shada’s research references writers who write in Arabic and Hebrew, Selma writes in English and Heba writes in English and Arabic.

Heba wrote in Arabic her whole life, including her blog, but she started writing in English during her MFA. She rejects shame for writing in English or people stating she is ‘not writing for her people’. Since she is in the diaspora, she has become more comfortable writing in English. She notes that Khalil Gibran “only felt comfortable writing in English because he got comfortable writing in Arabic and then translated those metaphors and visual devices”. She sees her literary consciousness as rooted in Arabic. When she writes, she writes for people who can relate to her in this way. She also shares that English is less emotional for her to write in. At this point, Shada asks Heba if because she once wrote in Arabic and now she writes in English, does she ever feel she can write something uncensored in English but she would conceal or veil it in Arabic?

Heba responds, “Certain topics I write about in English: queerness, love. But my consciousness in my writing doesn’t change a lot when I write in Arabic. People have written about lust and love a lot in Arabic before me, I feel like I am more inspired by the fact I read English texts more.”

The anthology text We Wrote in Symbols, brought the discussion to encoding symbolism and freedom of expression. Selma describes the book’s beginnings as a lockdown project. Like when she discovered Kanafani when she was younger, Selma describes the process as trying to free herself a bit. She would veer away from anything sexual or romantic, the revelatory subjects. She describes writing about sex difficult: “Pornographic language can be dulling and sound absurd. For some people it was exciting, for some revolting”. She speaks about the revelation of discovering Abdullah Al Udharri’s collection translated writing as a young woman, being shocked at the level of eroticism in such early works. “During the Arab Uprisings, so much of what came out of that later turned negative, but one thing that was positive were women who became more revelatory and outspoken about these kinds of topics. These are different ways of resisting, and, I thought, I could learn from them.”

Selma found listening to these accounts freeing. For people who have the luxury of having more than one language, it offered a freedom and a semi-disguise. She shares that for this reason, she likes to inhabit male protagonists, it gave her a chance to embody a character without being accused of it being autobiographical. She expects fluency from herself in Arabic, but it doesn’t come out that way. She describes herself as feeling more impoverished in that way, and developing a fluent tongue in Arabic is something she still aspires to.

Heba shares that she writes in English also because a lot of work she references in cross-solidarity work, resisting ‘Palestinian Exceptionalism’ and shares that there are other liberation movements she references. This language, English, she smiles, she uses it because she has full mastery of it. She doesn’t feel writers like Sayed Kashua should feel shame about writing in Hebrew. She finds it frustrating how writers like Mourid Barghouti or Ghassan Kanafani are interpreted in the West versus ‘back home’; she feels these differences are important in not mainstreaming one singular Palestinian representation. Shada and Heba discuss what moving away from ‘Palestinian Exceptionalism’ could look like, in drawing more strength from cross-solidarity work. Shada talks about Zizek’s much referenced theory, that the Palestinian can be “the universal subject” It reads the Palestinian struggle in terms of universality, that their struggle can represent the reference to the morals of oppression around the world. She feels it is necessary to consider, speaking directly to other Palestinians that “we are not the only victims. This is how we will be able to see we are not the other victims, we can connect to others around the world, in how the identity is re-imagined or re-configured, and this will be the change”.

Heba shares that she questions the term ‘Palestinian writing’ altogether. “Does it have to mention certain things to be considered a fit to the genre?” For her, writing as a Palestinian person, she has written lots of texts that are not rooted in the experiences of the occupation. For her, the queer issue, the class issue; that can be Palestinian writing. It cannot always be rooted in the disparity of her people.

Shada affirms the need for writing from new perspectives as Palestinians, through language. “The world of words that is important creates different worlds; we have to share some connection despite our differences. The ideological differences mask that sameness. We can uncover that through writing”.

With much to reflect on after the discussion, one of the last talking points in the discussion about oral history stayed with me. Heba says she thinks about oral history in her writing; the differences between what people say versus what people put on paper. Oral history is a field which affirms that accounts of history, like individual memory, are highly subjective and that testimonies with others are used to build shared meanings and symbols. She considers in her work, the people who have died, ancestors who gave us texts and those ancestors who gave us other creative works passed down through poetry and through singing. Her grandma was 1 years old in the Nakba, and she has heard her stories from her parents and relatives. The role of the Palestinian writer for her is to find ways to continue sharing and archiving stories, in a voice that feels free but always connected.