Throughout the film festival, we’ll be bringing you bitesize, behind-the-scenes, blogs to read. Written by Ja’far ‘Abd al-Hamid, a writer-director, with a focus on Arab British stories. His latest feature film, Kal & Cambridge, is scheduled for release next year.

Explore the full programme here, SAFAR Film Festival runs from 29 June to 9 July across 9 cities in the UK.

Saturday, July 1st 2023 screening of My Lost Country (2022)

As Iraqi-Chilean filmmaker Ishtar Yasin Gutierrez climbs the three steps to the stage at Cine Lumiere, to join festival curator Rabih El-Khoury before the screening of her film My Lost Country (2022), I can’t help but feel the benevolent energy she exudes.

The energy is more palpable as Ishtar introduces her documentary, talking briefly about the poignancy of showing her film in London, the city where her late father last resided. She concludes by dedicating the film to “our father”, motioning to her sisters in the audience.

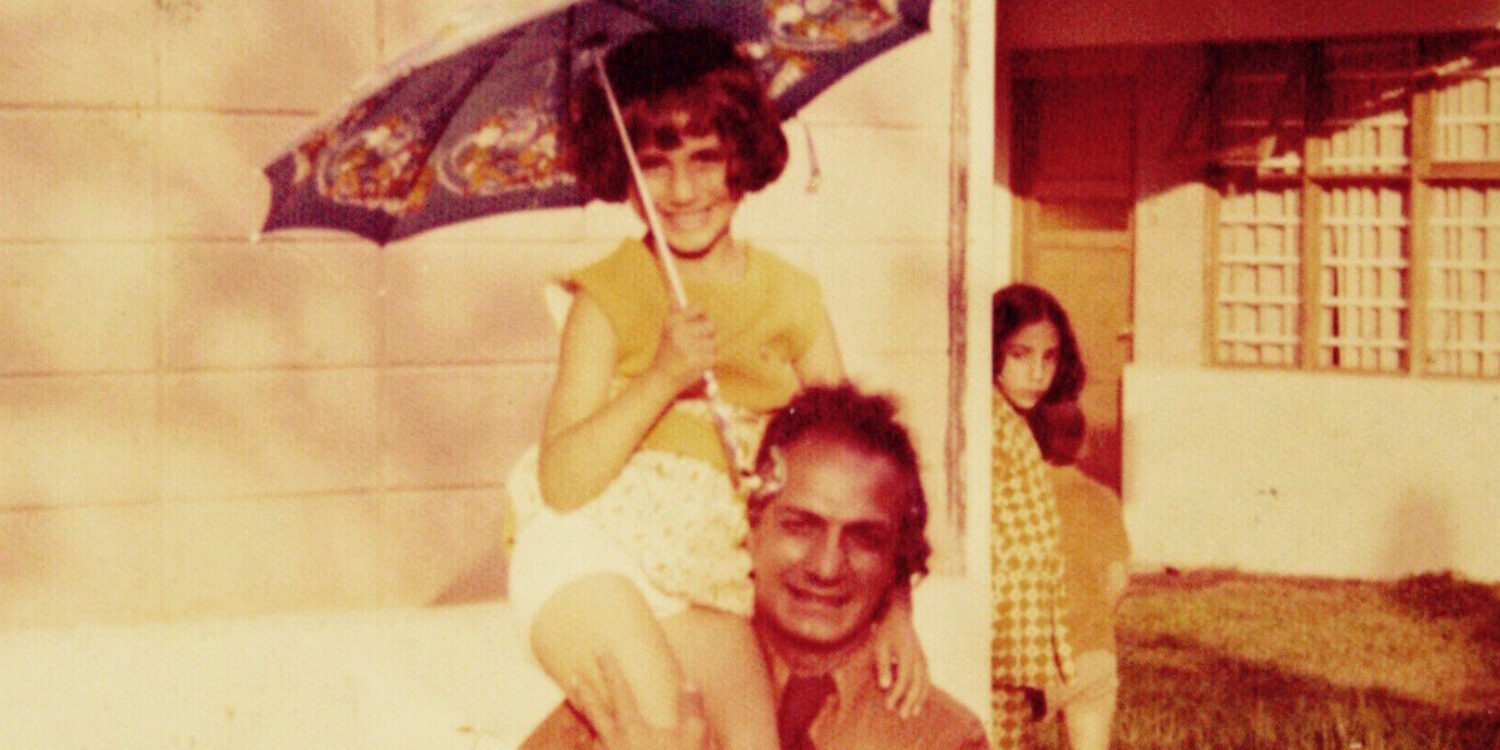

One of the first sequences in My Lost Country is of an audio recording of Ishtar at a very young age talking with her dad, Mohsen Sadoon Yasin. The screen is filled with an old colour photograph of Ishtar and her parent. “I have invented a story”, she announces to him in Spanish. “And to whom is it dedicated?” He asks her. “To my papito!” Charmingly responds the child.

Through family albums and videos, interspersed with archival footage, and newspaper clippings, Ishtar traces memories that at the outset seem to begin with her parents’ meeting; he an Iraqi theatre student and she a Chilean artist. Yet it soon becomes evident that Ishtar’s story is that of a whole generation of Iraqis born to exiled parents around the globe.

Throughout her childhood and teenage years, her dream of visiting her paternal homeland and meeting her grandmother kept being thwarted by her dad’s real fears for her safety, during Saddam Hussein’s rule. Later, with the invasion of Iraq, in 2003, “terrorists went to Iraq, because the Americans were there!” He painfully relates the catastrophe of the US invasion. “Give me one country that actually likes the Americans!” He asks rhetorically. “My country is lost!”

Eventually, Ishtar fulfils her wish of travelling to Iraq. She spends time at the Theatre Department of the Institute of Fine Arts in Baghdad, where her dad had been. She enters an empty classroom and opens its window, letting in the symphony of the city.

We see images of Mosul’s streets destroyed by the war against the so-called Daesh (ISIL), as Ishtar walks between ruins wearing a mask similar in its colour and composition to some of the statues and wood carvings that she had seen on a visit to the British Museum with her dad. As she moves, it feels as if she’s conjuring a connection between the earth on which she steps and the ancient civilisations that inhabited these very banks by the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.

On the soundtrack, her dad’s voice in his latter years recites an ancient Sumerian poem intercut with an old VHS video of him and a friend listening to the great 20th Century poet Muhammad Mahdi Al-Jawahiri reading his eulogy for his fallen brother, Ja’far. “Do you know or do you not know that the wounds of the victims are a mouth” [that relates the injustices visited upon them].

In the Q&A session, someone asks an eloquent question, talking of how Iraq is Ishtar’s other soul with which she is reunited through the making of the film.

Later, Ishtar ponders the relationship her dad had with his homeland. “In my father’s last years, he was unwell, and I felt that in his illness he was mirroring Iraq’s illness. He was feeling the pain of his country.”

Another great question is on how Ishtar managed to persevere in making this film, which she had earlier explained had taken her approximately fifteen years to complete.

“I had to make it; I didn’t care if I didn’t have the funds for it, even if I had to make it by hand.”

When I go up to Ishtar to thank her for this epic undertaking, I share my reaction to watching in the film an old clip from Soviet TV, during her time studying film in Moscow in 1986. She was all smiles, responding in halting Russian to the reporter’s off camera questions. “And yet,” I confide to Ishtar, “there is so much pain behind those smiling eyes!” We both well up as we recognise our collective legacy as kids of Iraqi exiles.

We are interrupted by one of Ishtar’s cousins needing to say goodbye, “we need to catch the last train!” She explains apologetically.

Walking towards the door, I say hello to Amani Hassan, Programme Director at the Arab British Centre. Like me, she is moved by My Lost Country.

We are joined by the Egyptian director, Hala Galal, whose brilliant documentary From Cairo (2021) unspooled at this auditorium on Friday. Visibly touched, she concurs, “that was really something!”

Images: Ishtar Yasin Guttierez & London Event Photographer, Kevin Moran