The Broad in Black with a Beretta, My Wife is Hippy and other tales from Arab cinema

An exhibition of vintage posters and contemporary Middle Eastern art inaugurate the second Safar Festival of Popular Arab Cinema, at the ICA.

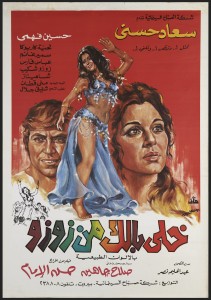

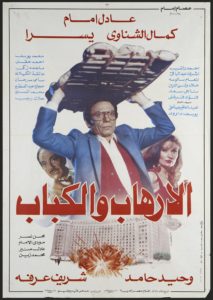

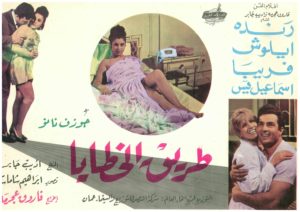

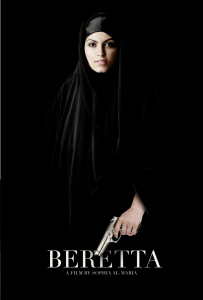

A lurid belly dancer, a dishevelled woman screaming, a couple in a lascivious embrace, Hitler, a motorcycle-riding oud-player (in the sky, no less) and a broad in a black abaya packing a Beretta… These are just some of the images from original Egyptian film posters and contemporary art in Whose Gaze Is It Anyway?, the exhibition which inaugurates the second Safar Festival of Popular Arab Cinema, at the ICA.

‘Are we looking from within or are we looking from outside, and whose reflection or representation is more potent?’ asks Safar’s artistic director and exhibition curator Omar Kholeif.

He considers the nine rare Egyptian posters created between 1959 and 1993, displayed in Britain for the first time. ‘Their reflection is meant to challenge particular notions from within. I never like to think about binaries. For me it’s more about poking fun at the fact that we assume there is a tension between looking within and looking outside.’

Nearly all of the vintage movie posters, bar one, were distributed across the Middle East the year the Egyptian film was released. They were painted by local artists also known for producing lurid pulp fiction book covers for pirated domestic editions. Like the studio photographers of their day, these artists were for the most part nameless, badly treated and poorly paid. They ranked low down in the hierarchy of Egypt’s glamorous movie industry. In fact, it makes more sense to see them as a separate homegrown creative industry, which operated out of many Arab capitals. In Beirut, for example, most of the cinema poster painters were Armenian.

Kholeif sees the posters as vibrant examples of populist art in their own right, which reveal ‘how a sense of local identity was marketed, articulated and represented. Actually it is also very different from how you would imagine images of the region. I think people would expect images of oppressive women with niqabs.’

Both the poster art form and the films reflect historic changes in the Arab world and aesthetic developments in Egyptian cinema. ‘I begin with Khalli balak min Zouzou (Watch Out for Zouzou), an iconic film that represents the end of the liberal era right before the rise of the Islamic era,’ Kholeif points out. ‘Al Asfour (The Sparrow) harks back to the Six-Day 1967 war and a more depressing era of the crushing of the Pan-Arab ideal. Al-irhab wal kabab (Terrorism and the Kebab) was the 1990s and the growth of speculation about terrorist groups and fundamentalism, which is in stark contrast to Khalli balak min Zouzou.

‘Bidaya wa nihaya (The Beginning and the End), with Omar Sharif, was the beginning of Arab realism in cinema. Bab al Hadid (Cairo Station) was the start of a kind of referencing of Italian new realism in Egyptian cinema by Youssef Chahine, in 1958. Iskandariya, Leh?(Alexandria, Why?) is the first of the autobiographical trilogy by Chahine, seen as the auteur of Arab cinema, but there was also very much a French influence in his work; he aspired to the European canon and was much more appreciated in Europe.’

The posters come from an extensive film and memorabilia archive of Arab cinema in a high-rise basement in Beirut. It was created by the collector Abboudi Bou Jaoudeh whose earliest pieces date back to the 1930s. One of the ‘envoys’ Kholeif sent to the archive was Lebanese artist Mounira Al-Solh based in Amsterdam. She curated two vitrines, or display cabinets, for the exhibition, which include movie brochures – the most evocatively titled one being ‘My Wife is Hippy’ – used for movie tie-ins and product promotion.

Al-Solh also included archive black and white production stills. Here too the gaze of the exhibition is multitudinous. In black and white photos Egypt’s tragic film diva Soad Hosni looks out from her bed; a transvestite-looking figure gets ready for camera; and a male actor knowingly winks before ravishing a starlet.  Al-Solh, Kholeif and the exhibition’s other contemporary artists are from a generation whose relationship with Egyptian cinema has influenced their work. Al-Solh’s selection from the Abboudi archive encapsulates the sense of escapism Egyptian films gave her when she was a child growing up during Lebanon’s civil war. ‘You’ll see within the images,’ describes Kholeif, ‘a real potent sexuality, celebration and frivolousness.’

Al-Solh, Kholeif and the exhibition’s other contemporary artists are from a generation whose relationship with Egyptian cinema has influenced their work. Al-Solh’s selection from the Abboudi archive encapsulates the sense of escapism Egyptian films gave her when she was a child growing up during Lebanon’s civil war. ‘You’ll see within the images,’ describes Kholeif, ‘a real potent sexuality, celebration and frivolousness.’

In a short film, another Lebanese artist Raed Yassin tells the story of his father’s addiction to disco and his career in the Egyptian horror film industry. He does so by using film clips of an actor who has the same name as his father, Mahmoud Yassin. Domestic Tourism II, by Maha Maamoun, is the sixty-minute film that inspired the exhibition’s title. Through footage from Egypt’s tourist industry and television and advertising broadcast on Arabic satellite channels, Cairo-based artist Maamoun explores romantic and nostalgic notions of the country. Expect the pyramids.

At the exhibition’s conceptual heart is the painting of a woman in a black abaya holding a Beretta semi-automatic pistol on canvas. It is a poster that was created for an unrealized film. Beretta, a rape revenge thriller in the vein of cult cinema by the Qatari-American artist and novelist Sophia Al-Maria, has been stuck in pre-production for the past three years. The film was born out of her experiences of being continually harassed as a woman while living in Cairo. Kholeif explains, she ‘wants to produce this feature film to be seen on late night TV by all the boys who harassed women.’

From Al-Maria’s notebooks, shown in the exhibition, Kholeif and poster designer Sam Ashby produced Beretta, the poster, which was hand-painted – not in Egypt but in China because they couldn’t find an Egyptian poster painter. The art form that epitomised the world of Egyptian cinema in the past, and was known throughout the region, has been overtaken by digital reproduction. Behind the Beretta poster is the aesthetic point that the archive has entered public consciousness, and that the artefact sometimes appears first before the finished product.

From Al-Maria’s notebooks, shown in the exhibition, Kholeif and poster designer Sam Ashby produced Beretta, the poster, which was hand-painted – not in Egypt but in China because they couldn’t find an Egyptian poster painter. The art form that epitomised the world of Egyptian cinema in the past, and was known throughout the region, has been overtaken by digital reproduction. Behind the Beretta poster is the aesthetic point that the archive has entered public consciousness, and that the artefact sometimes appears first before the finished product.

At a time when the news is filled with scare-mongering stories about teenage Somali girls running away from their immigrant families in America to go and fight for the Islamic State in Syria, the Beretta poster plays on Western paranoia. ‘In the historic [posters] you don’t see any abayas whatsoever but here you see an abaya, so you know it is a contemporary situation.’ Kholeif observes, ‘Then you see a gun and the gun contradicts the stereotype in a very particular way.’ Another of Al-Maria’s pieces Rape Gaze, on iPad, examines popular Egyptian film posters and how the woman was ‘always raped’ through the image of the man. With all its hilarity and fun, the deconstructed view shown in Whose Gaze Is It Anyway? remains deathly serious.

– Malu Halasa.

For more information on the exhibition, please click here.

London-based journalist writer and editor Malu Halasa is our writer-in-residence. Keep your eyes peeled for her posts in the run-up and during the festival.