Celine Luppo McDaid is the Donald Hyde curator of Dr Johnson’s House, our collaborators and host of the London’s Theatre of The East exhibition running from 8 November 2019 – 15 February 2020. This blog is taken from ‘London’s Theatre of The East: Essays on the Exhibition by Artists and Academics’, which will be available to buy for £5 as part of the exhibition.

Often cited as a great advocate of London and famous for the aphorism ‘when a man is tired of London, he’s tired of life’, Samuel Johnson (1709–84) was actually born in Lichfield, Staffordshire, in his father’s bookshop, where his love of literature first began. An avid reader with the capacity to commit to memory what he read, he attended Pembroke College, Oxford University, in 1728, although ailing family finances meant he had to leave after just one year. Johnson returned to Staffordshire and tried his hand as a school master, even opening his own school, Edial, with his new wife, Tetty, in 1735, though this would close within two years, having failed to attract many students. Johnson formed a life-long friendship here with one pupil, however, who would become the star of the 18th-century stage, David Garrick. It was with Garrick that Johnson decided to come to London in 1737 to establish himself as a writer. Once here, he made the city his home until his death nearly 50 years later.

Throughout the course of his literary career, Johnson would excel as an essayist, literary critic, and, of course, as the author of the first comprehensive English dictionary in 1755. Johnson was also a gifted linguist and his first published book was a translation from a French copy of A Voyage to Abyssinia (1735), written by a Portuguese Jesuit priest, Fr. Jerome Lobo. This account of Lobo’s experience in Abyssinia (present day) contains observations about his travels, and examines the customs, dress, and hospitality of a country and culture unfamiliar to most Europeans at this time. Johnson’s selection of this work for translation demonstrates his interest in exploring, albeit through travel accounts of foreign countries and civilisations. In the preface to this book, Johnson makes an observation of his own:

‘The Creator distributed both vice and virtue equally throughout the world’.

The use of the adverb ‘equally’ is significant: it consciously contradicts the popular belief amongst some Europeans that there was a ‘natural hierarchy’ to humanity, with Europeans at the top in terms of their ‘superior civilisation’. Johnson did not prescribe to this belief and would return to this conviction throughout his life, believing rather in the value of travel accounts in exploring unfamiliar or ‘exotic’ cultures. He advocated the reading of authors, rather than historians or politicians, as the best way to gain an understanding of and insight into the values of a different culture, stating in the preface to his Dictionary of the English Language (1755) that ‘the chief glory of every people arises from its authours’ [sic].

His first major original composition, however, was theatrical, and he actually came to London with the intention of becoming a playwright. Johnson’s mentor since childhood, Gilbert Walmesley, a Registrar of the Ecclesiastical Court in Lichfield, thought highly of the young writer’s talent and supported his intentions. The day Johnson and Garrick set off for London, Walmesley wrote to a friend there, commenting on his potential:

‘He [Garrick] and another neighbour of mine, one Mr. Samuel Johnson, set out early this morning for London together. Davy Garrick is to be with you early next week, and Mr. Johnson to try his fate with a tragedy, and to see to get himself employed in some translation, either from the Latin or the French. Johnson is a very good scholar and poet, and I have great hopes will turn out a fine tragedy-writer.’

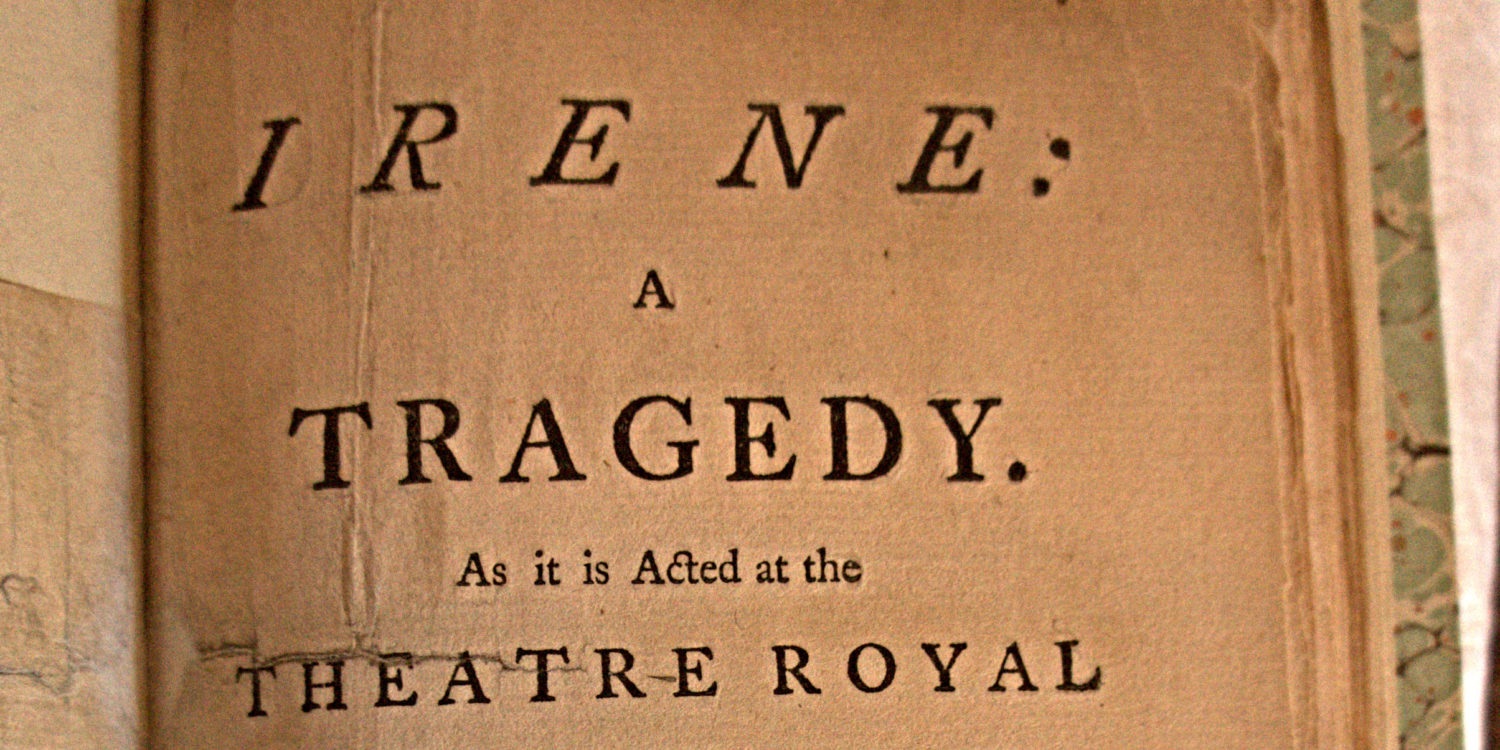

The tragedy referred to here is Johnson’s play, Mahomet and Irene, or Irene as it would later become known, which he largely composed whilst at Edial. The play is set during the fall of Constantinople and tells the tale of the Sultan Mahomet, who conquers the city in 1453 and captures a Greek Christian named Irene. The story is not Johnson’s creation, it dates back c. 150 years to Richard Knolles’s Generall Historie of the Turkes (1603) and was the source of several plays and poems before Johnson’s interpretation. Although Irene ultimately dies in every account, Johnson adapts the story to explore the theme of Irene’s dilemma. His Mahomet offers Irene a deal: if she converts to Islam, he will be able to preserve her life and give her power at his court. This allows Johnson to focus more on the ‘female voice’ and her powers of reason, where Irene understands her role and the implications of accepting or rejecting Mahomet’s offer, while voicing the inner turmoil the question of her religious conversion provokes. Johnson explores her humanity, and that of Mahomet, who sees Irene not as a trophy of war but as someone he truly cares for – Johnson explores his characters’ anguish and elevates Irene from being a mere pawn in a male world of power, dominance and political engineering at court.

Johnson moved to London in the hope of staging this play in one of the patent theatres. It was presented to Charles Fleetwood, manager of the Drury Lane Theatre, who turned it down. According to Johnson’s biographer James Boswell, this was ‘probably because it was not patronized by some man of high rank’. The lack of financial backing from a wealthy and established patron made it highly unlikely that managers would risk the cost of producing a play by an unknown playwright.

Johnson’s Irene was finally performed at the Drury Lane Theatre 12 years later, in 1749, the year that his friend and pupil David Garrick became sole manager. This appears to be a personal favour to Johnson, who was in the throes of compiling his Dictionary, had missed the deadline for its completion and was fast running out of funds to support the project or his household. Relations between the author and the actor became strained, however, owing to Garrick’s proposed amendments as the play’s director. Garrick understood the expectations of theatre-goers well, and knew that regardless of literary merit, the play would not be suitable for the stage without some alteration. Boswell records the tension between the two:

‘In this benevolent purpose [Garrick] met with no small difficulty from the temper of Johnson, which could not brook that a drama which he had formed with much study… should be revised and altered at the pleasure of an actor… ‘The fellow [Garrick] wants me [Johnson] to make Mahomet run mad, that he may have an opportunity of tossing his hands and kicking his heels.’ He was, however, at last, with difficulty, prevailed on to comply with Garrick’s wishes, so as to allow of some changes; but still there were not enough.’

Although the play ran for a respectable nine nights, allowing for three benefit performances where a handsome profit of £300 was made for Johnson, it was not well received, and would not be staged publically again. This account from a member of the audience on the opening night perhaps reveals why:

‘Before the curtain drew up there were catcalls whistling, which alarmed Johnson’s friends. The Prologue, which was written by himself in a manly strain, soothed the audience, and the play went off tolerably, till it came to the conclusion, when Mrs. Pritchard, the heroine of the piece, was to be strangled upon the stage, and was to speak two lines with the bow-string around her neck. The audience cried out ‘Murder, murder.’ She several times attempted to speak, but in vain. At last she was obliged to go off the stage alive.’

Johnson was furious, and had to concede to Garrick’s voice of experience: on subsequent nights the strangling took place offstage, with chilling effect.

Despite Johnson having a reputation as a talented writer by this time, contemporary reviews praised the language and moral of the play but agreed that it lacked dramatic impact. Johnson would never attempt to write a play again.

Although Irene was not the desired success, Johnson returned to the theme of exotic tales, travels and foreign cultures in various essays (published in The Rambler / The Idler / The Adventurer) and in his poetry, most notably The Vanity of Humans Wishes (1749). An imitation of Satire X by the Latin poet Juvenal, Johnson attempts in this poem to characterise the human condition the worldwide:

‘Let observation with extensive view,

Survey mankind, from China to Peru;

Remark each anxious toil, each eager strife,

And watch the busy scenes of crowded life;’

Johnson’s adaptation focuses on the human trait of the futile pursuit for greatness, concluding that a good life depends rather on the possession of robust moral values which is essential to living a good life. Johnson most notably takes up these themes in his philosophical story, The Prince of Abissinia: A Tale (later known simply as Rasselas) in 1759, where he returns to the landscape of his first published work (Lobo’s account of the same country). Johnson’s only novel, this was the last piece he wrote in 17 Gough Square, and was again born of the need for money (this time, to pay for his mother’s funeral). Johnson uses the characters and narrative to present an allegory about the value of the pursuit of human happiness, questioning whether it is attainable on earth. In order to find the answer, the protagonist, Rasselas, and his companions leave the comforts and luxury of their home to explore new countries and civilisations, commenting on their customs and values as they progress. The numerous people they meet, not least their philosopher-poet guide, Imlac, teach them about the importance of learning many languages and sciences. As part of this education, Imlac relates his encounters in Syria and Palestine, inspiring the young Prince Rassalas to visit:

‘“When,” said the Prince with a sigh, “shall I be able to visit Palestine, and mingle with this mighty confluence of nations? Till that happy moment shall arrive, let me fill up the time with such representations as thou canst give me. I am not ignorant of the motive that assembles such numbers in that place, and cannot but consider it as the centre of wisdom and piety, to which the best and wisest men of every land must be continually resorting.”

Although Johnson never became the playwright he initially hoped to be, he was always fascinated by the theatre, along with travellers’ tales and distant civilisations, he firmly beleived that the human condition was a shared universal state, not confined by language, customs or borders. Through the project London’s Theatre of the East, we at Dr Johnson’s House are excited to be revisiting Johnson’s Irene both on the page and on the stage, and to be holding the first public performance of the play in 270 years as part of our exhibition programme. We are thrilled to be collaborating with 21st-century artists and authors of Arab – British heritage on this project, continuing the long tradition of reinterpreting and retelling the tale of Mahomet and Irene and the themes arising from this drama, and the long history behind it of Anglo – Arab cultural exchanges.