An intimate and honest portrait of home.

Review by Layla Ali.

With thanks to Bertha DocHouse for the ticket to the screening.

The screening took place in July 2023.

***

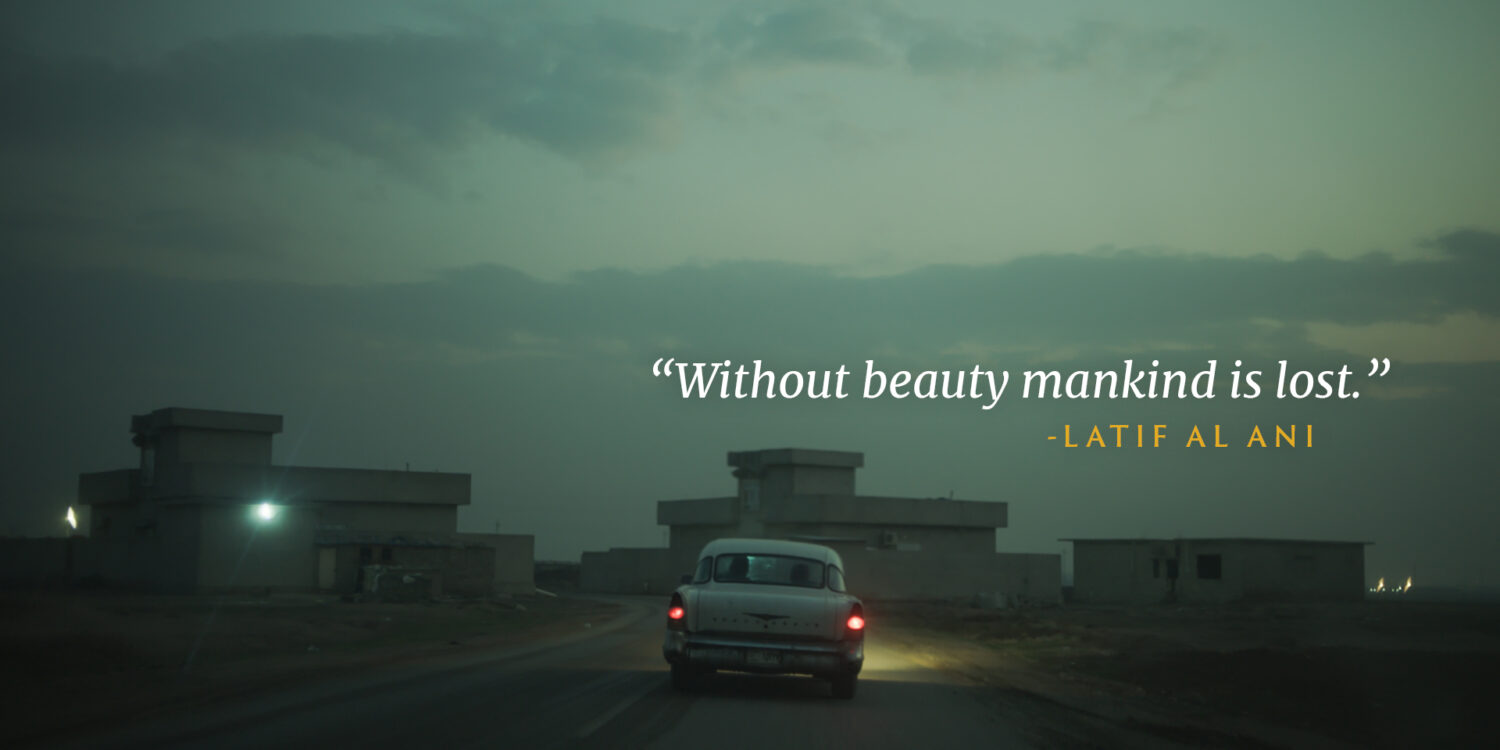

Filmed over a period of five years, Belgian-Kurdish filmmaker Sahim Omar Kalifa’s documentary follows the ‘father of Iraqi photography,’ the late Latif al-Ani, on a journey through his beloved homeland, in search of the places and people he once photographed.

The journey is an intricate one, underpinned by the unifying thread of al-Ani’s meticulously, lovingly pieced together and preserved archive of Iraq’s recent history.

Sadly, only 200 of an estimated 200,000 photos survive. Despite this, having started his career with the Iraq Petroleum Company, before working for the Iraqi Ministry of Culture, and eventually leaving Iraq for a period, al-Ani’s work beautifully captures a subject in constant flux. The film encapsulates this well, paying tribute to Iraq’s diversity and complex history in its exploration of Kurdistan, Mosul, Erbil and the Marshes of the south.

As they travel across the country, Kalifa powerfully showcases al-Ani’s strikingly clear memories of Iraq’s past, giving detailed accounts of what and where things used to be, and how they have since changed. At times, he seems to remember more than the people he stops to talk to along the way.

Scenes filmed in Mosul and the Marshes are particularly moving, with both Kalifa and al-Ani struggling with the emotional burden of Mosul’s destruction. Kalifa depicts al-Ani’s fondness for the Marshes as he recounts their history and notes the impact of the climate crisis.

It is unclear whether al-Ani, Kalifa, or both, are unwilling to discuss the historical and political background behind the photographs in much detail, but this seems beside the point, and use of an English-language narrator throughout provides sufficient context for an unfamiliar audience. Al-Ani’s love for both photography and his country are the main characters of this film; his exploration of Iraq’s landscapes, monuments and people convey a burning desire for Iraq to move forwards, or perhaps backwards, to its, and his, heyday from the 1950s to 1970s.

Themes of progress and regression, humankind’s power to create and destroy, and the contrast between urban and rural weave a loving, but honest, portrait of Iraq as only someone who truly knows it could paint. Certainly, al-Ani’s initial disdain for Kalifa as someone who ‘doesn’t know much about Iraq or photography,’ is disproved by the synergy between film and photography that Kalifa so skilfully creates.

The film’s ending is complimented nicely by the choice of music, and provides an appropriately sentimental close to the touching summary of a life spent in service to, and search of, a beloved homeland.