IN HIS OWN WORDS

Ali Ferzat on Art, Censorship, freedom and the revolution in Syria.

I think I was five when I started drawing cartoons and making up satirical stories about what was taking place in my own house. I didn’t choose to be a caricaturist. I was born like this. When I was twelve years old, I had my first cartoon published in Al Ayyam (‘The Days’). The owner had no idea I was only in the sixth grade!

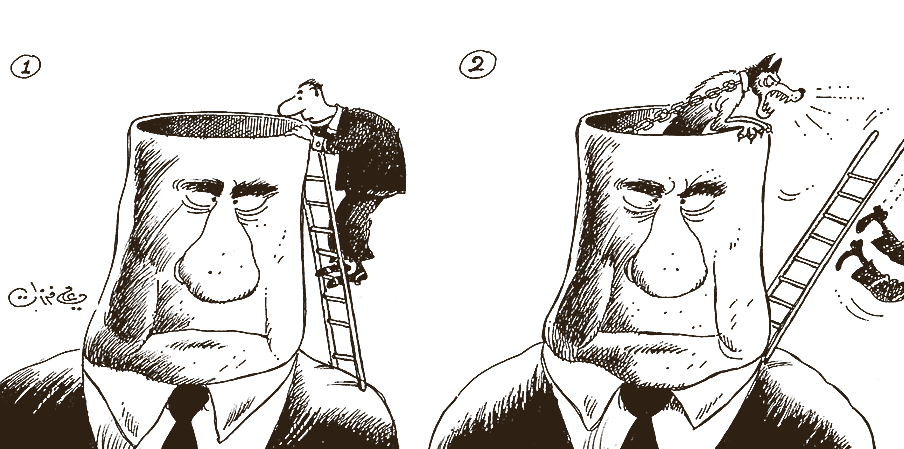

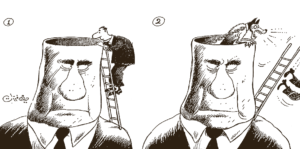

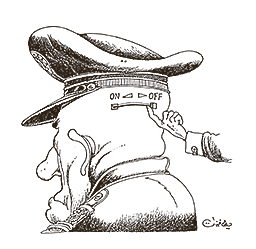

My cartoons touch on people’s lives, and people trust them. They became like a lantern that people look to. My caricatures were devoid of speech and used symbols, and because of that I could survive censorship in my country and publish some of them freely. This approach also gave my work an international appeal since it relied on images anyone could understand – without the barrier of language intervening. So while I was trying to avoid censorship at home, I unintentionally gave my cartoons wings that made them fly off to the rest of the world. In this way I managed to get the voice of the people inside Syria to the international community, basically through shared channels of human interest.

My early cartoons showed actions and behaviour based around a general theme, like hunger. Little by little my cartoons became very popular and people bought the newspapers for the cartoons. From the early to late 1970s, I published a daily editorial cartoon in the official newspaper Al Thawra (‘Revolution’). Sometimes the managing editor failed to understand the symbolism in the cartoon, and after it was published, he would get a shouting phone call from the government. So a new procedure was put in place. First, the editor in chief had to look at the cartoon. If he approved it, he had to send it to the general manager of the newspaper. Whether or not he approved it, or found it too controversial or difficult to understand, he had to send it to the minister of information [in charge of media]. At that time, the minister was a bit of an ass, and he would say ‘yes’ because he didn’t understand it. The next day people saw the cartoon and immediately comprehended its meaning because it was just a matter of common sense. Then the angry phone calls would start all over again.

One time, the general manager sat for a long time contemplating one of my cartoons, unable to detect exactly why he should censor it. But he felt he needed to, simply because he didn’t trust it, so he looked at me and said, “Just promise, swear to God, there is nothing bad in this.” In 1980, I had a meeting with a former prime minister who said, “Can we give you a salary so that you will stay and do nothing. Your cartoons undo all of our work on the first page.”

For me, drawing is a means to an end and not a purpose by itself. The artist is always the one who produces an idea, but if that artist is not living within his own community and going through what the people there are going through, then how could he understand what’s going on and reflect it? To be a good artist or painter, you have to express the feelings and experiences of the people. Art is all about living with your own people, and having a vision about what they need as well. You can’t sit in your own room isolated behind your window and draw about life. It doesn’t work like that.

The concept of red lines depends on the culture and the level of civil liberties achieved in a country. Europe and America are definitely different from the Middle East. Freedom of the press should imply a responsibility rather than something undertaken chaotically. It’s not like I do whatever I feel like doing at whatever moment I feel like doing it, regardless of the consequences. It is a matter of moral commitment. It’s relative; you always have to find the right balance. Some newspapers refrain from nothing and call it ‘freedom’, while other newspapers even censor human interest stories. I see both as bad. Too much suppression in the name of commitment is not good, but by the same token too much unethical commitment in the name of freedom is not wise either. They are both the same.

At the beginning of Bashar al-Assad’s presidency, I used to communicate directly with him beyond the control of the mukhabarat, the secret police, and I was happy about that. I tried to get him to meet other artists. I remember when he first walked into my exhibition at a cultural centre – a tall dude with a large entourage. He asked me how he could access what the people were thinking

and I told him to just talk to them. When he asked me what my plans were for the future, I said I was going to start a satirical newspaper and wanted to tackle every aspect of the government. He said I might as well go after the parliament as well.

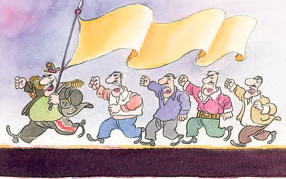

When the Ba’ath Party initially came to power in 1963, it closed all private and independent newspapers and publications. My newspaper, Al Doumari (‘Lampl ighter’), was the first independent newspaper in nearly twenty years. One of our themes was corruption. A scandal had erupted with IV serums because they were out of date and yet they were still being used in a hospital in Damascus. So I drew serum bags filled with fish. The newspaper was allowed to publish for two years and three months exactly. Then it was banned. During this period, there were two attempts to arrest me and 32 cases were filed against the newspaper in the courts. Pro-Ba’ath students demonstrated in front of the offices of Al Doumari. People were prevented from advertising in it. By then, I was never able to reach Bashar, and when I finally did get through, he told me to handle my own problems. Now we’re working on publishing a new Al Doumari outside of Syria that will complement the coverage of the revolution from within.

Excerpt from ‘Ali Ferzat: In His Own Words’ – Ali Ferzat in conversation with Malu Halasa | Translated from Arabic to English by Leen Ziyad | Article courtesy of Prince Claus Fund taken from the accompanying exhibition publication Culture in Defiance curated and edited by Malu Halasa.

For the full article and others, download Culture in Defiance publication here.

For more information on Culture in Defiance exhibition click here.

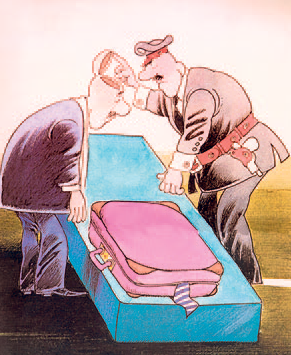

Images above: all cartoons by Ali Ferzat

About Prince Claus Fund

The Prince Claus Fund was set up on 6 September 1996 as a tribute to Prince Claus’s dedication to culture and development. The Fund believes that culture is a basic need and the motor of development. The Fund’s mission is to actively seek cultural collaborations founded on equality and trust, with partners of excellence, in spaces where resources and opportunities for cultural expression, creative production and research are limited and cultural heritage is threatened.

The Prince Claus Fund supports artists, critical thinkers and cultural organisations in spaces where freedom of cultural expression is restricted by conflict, poverty, repression, marginalisation or taboos.